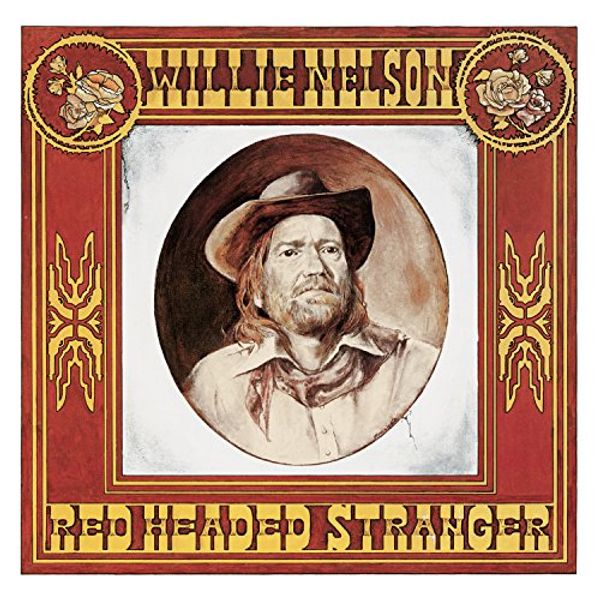

Willie Nelson - Red Headed Stranger

‘Red Headed Stranger’ not only catapulted Willie Nelson to superstardom, but it also marked his first artistic triumph on his own terms. Its impact on country music has been incalculable.

Link copied

By late 1974, Willie Nelson’s career wasn’t exactly faltering, but it was certainly starting to look like he’d hit a wall. At the time, Nelson was universally regarded within the music industry as an exceptional songwriter on the strength of ‘Crazy,’ his timeless classic made famous by Patsy Cline, but he wasn’t quite achieving sales commensurate with either his talent or his stature.

As a result, Nelson wasn’t automatically getting the benefit of the doubt from record executives. The feeling was mutual - Nelson had famously left Nashville for Austin in 1972 feeling disillusioned with the Nashville establishment’s sensibilities, which he saw as rigidly commercial and formulaic. And in short order, with his first album for Atlantic Records, 1973’s Shotgun Willie, he struck out on his own terms and helped jump-start the burgeoning outlaw country movement.

The following year, however, after just one more album for Atlantic (the modestly successful Phases and Stages, which had been recorded at Alabama’s legendary Muscle Shoals studio), the label shuttered its country division and dropped its entire country roster. At that point, an enthusiastic Bruce Lundvall, then-president of Columbia Records, seized on the opportunity to sign Nelson.

But, as Lundvall recalls in his 2013 biography Bruce Lundvall: Playing by Ear, when he turned to Billy Sherrill, Columbia’s head of A&R in Nashville at the time, Sherrill strongly advised him against inking the deal. Nevertheless, not only did Lundvall go ahead with the deal, he agreed to terms giving Nelson total creative control, an unprecedented arrangement negotiated by Nelson’s manager Neil Reshen (who also managed fellow iconoclasts Waylon Jennings and Miles Davis).

Indeed, when Reshen and Jennings went to Lundvall’s office to play him an acetate disc of Nelson’s newly-finished 18th studio album Red Headed Stranger, it must have seemed to Lundvall that leaving Nelson to his own devices had been a mistake. In stark contrast to the string arrangements that Nelson’s old label RCA had so often imposed on his music, the new material consisted of bare bones arrangements, with Nelson and his guitar backed primarily by piano and drums courtesy of Nelson’s sister Bobbie and his longtime drummer Paul English. (Discreet flourishes of mandolin, harmonica and bass only accentuate the spartan atmosphere.)

Though Lundvall’s interest was piqued by the performances, from his perspective the album sounded like an unfinished demo that had been recorded in Nelson’s living room. Lundvall’s reaction reportedly drew a heated rebuke from Jennings, who got up and insisted that “That’s what Willie’s all about.”

Red Headed Stranger had actually been cut at a studio, but we can’t really blame Lundvall; he didn’t have the reference point that we have today. Records simply weren’t made this way back then. And even if Nelson had set the outlaw-country template with Shotgun Willie, the production approach on Red Headed Stranger was downright heretical by comparison.

By any measure, Red Headed Stranger shattered the mold in ways that continue to reverberate today. There’s certainly an argument to be made that, in the near-half century since the album’s release on the first of May 1975, entire generations of musicians owe their existence to the first thirty seconds alone of opening number ‘Time of the Preacher,’ with its sweet-sounding piano chords in a gentle waltz with Nelson’s guitar strums.

Predictably, however, Sherrill hated what he heard. Had he gotten his way, Columbia would have simply refused to put the album out. Lundvall, to his credit, remained open-minded. He took the music home for the weekend, where he played it repeatedly and promptly fell under the music’s spell. In an amusing twist, Lundvall called the Columbia staff into a meeting the following week to defend the album, and to explain to them that the label was going to stand by Nelson’s vision.

“It’s not going to sell,” he remembers telling the staff, “but it’s special.”

Lundvall was right in one respect, but he was dead wrong in another - against conventional industry wisdom, Red Headed Stranger reached number one on the Billboard Top Country Albums chart and sold two million copies. It also, paradoxically enough, catapulted Nelson to superstar status whilst simultaneously cementing his place as an uncompromising rule-breaker intent on doing things his own way.

Looking back, though no one could have predicted such a smash success, it’s not difficult to see why the album struck a universal chord. Sure, Nelson structured Red Headed Stranger as a concept album that hovers in a hazy space somewhere between dream, fable and myth - something of a departure from country music’s ordinary everyday grit - but he presented the storyline in utterly relatable terms.

The music itself, meanwhile, unfolds with the lilting ease of a lullaby. In fact, Nelson liked to sing the title track, a murder ballad written two decades prior by critic Edith Lindeman and radio announcer Carl Stutz, to his young children at bedtime. The song, which recounts the story of a man who kills his wife and her lover, had captivated Nelson since his days as a radio DJ. On a drive from Colorado back to his native Texas after leaving Nashville, he was struck with the inspiration to expand the scope of the story. And with that, country music’s first concept album was born.

Nelson wrote barely a third of the album himself, but he makes it unmistakably his own via his voice, delivery and accompaniment. His rendition of Hank Cochran’s ‘Can I Sleep in Your Arms’ conveys regret and longing for another’s touch with a humanity and beauty that still stuns many years later. And it’s to Nelson’s eternal credit that he could relay such heavy themes with such a graceful touch. Where his outlaw peers were often enshrouded by a dark mystique, Nelson could sound approachable - even angelic - while plumbing the depths of the human spirit.

Red Headed Stranger’s central figure, a fallen-preacher antihero wandering the countryside on a black horse in a state of perdition, echoes centuries upon centuries’ worth of archetypal legends that haunt the edges of modern consciousness. (To fully do the scope of the album justice, one needs to read Chet Flippo’s longform review in the September, 1975 issue of Texas Monthly.) It would be facile to suggest that Red Headed Stranger’s protagonist was merely supposed to function as a metaphor for Nelson as an artistic outsider. Perhaps that was part of the inspiration, but he tapped into something far deeper and far more resonant.

In 2003, Nelson’s early-’60s Nashville demos for Ray Price’s publishing company surfaced on a must-hear compilation titled Crazy: The Demo Sessions. For anyone who’s known Nelson as an eternally smiling, buddha-like hippie elder, the unflinching despair he reveals on Crazy comes as a revelation. When Waylon Jennings declaimed that “That’s what Willie’s all about,” he was referring to the sheer creative power Nelson could marshall using minimal frills.

It took Nelson eighteen tries, but he finally captured his true essence on Red Headed Stranger, a monumental work whose impact on country music has been incalculable.

10/10.

Willie Nelson's Red Headed Stranger was released via Columbia. The record is part of an exclusive boxset from Holler's friends at Vinyl Me Please. You can purchase this below:

Items featured on Holler are first selected by our editorial team and then made available to buy. When you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.,

For more reviews from VMP's Willie Nelson Anthology, see below: