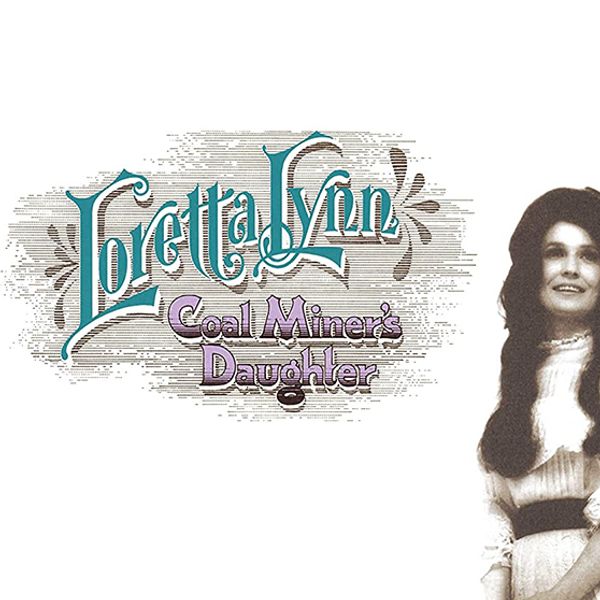

Loretta Lynn - Coal Miner's Daughter

By Helen Jerome

Coal Miner's Daughter is an understated masterpiece of concision, drama and imagery – every verse a short story that’s rarely been equalled, even in a genre where storytelling and authenticity are the most prized assets.

Link copied

When President Obama gave Loretta Lynn the Medal of Freedom in 2013 - the nation's highest honour recognising significant achievements in politics, world peace, science and culture - he noted that she began writing her own songs with a $17 dollar guitar. “With it”, he said, “this coal miner’s daughter gave voice to a generation, singing what no one wanted to talk about and saying what no one wanted to think about.”

Loretta Lynn may now wear the tag of Living Legend and have a statue outside the Ryman Auditorium. She may also have the big hair and extravagant dresses to match her stand-out voice and performances. But when it comes down to it, her career has always been about her humble life story; something that’s perfectly expressed in 1971’s Coal Miner’s Daughter, a record which might just represent the peak of her singular songwriting and creativity.

When Loretta signed her first recording contract in 1960, she already had a handful of kids and an immoral husband who’d married her when she was just a teen. Despite his abusive and adulterous behaviour, she stuck with him – realising that their life was fodder for her songwriting and her delivery. “The more you hurt,” she said, “the better the song is. You put your whole heart into a song when you’re hurting.”

Such life experience would always find its way into Lynn’s songwriting. When her career took off, women’s work was shockingly underpaid, with one-fifth of Americans living below the poverty line. Her father’s generation had also worked in appalling conditions – in his case as a coal miner – and he passed away from black lung, the miner’s disease, aged just 52.

Ten years down the road, when Lynn was making her 15th album, President Richard Nixon said: “I’m not for women in any job. I don’t want any of them around.” Despite the then-president's notions, women were beginning to find their voice - women’s lib was rising and creating a platform for these stories to be told - and as she’d proven before, Lynn wasn’t afraid of tackling difficult subjects.

On Coal Miner’s Daughter, every tiny, stark, heartfelt memory of Lynn’s life until that point came flooding to the fore. It’s an understated masterpiece of concision, drama and imagery – every verse a short story that’s rarely been equalled, even in a genre where storytelling and authenticity are the most prized assets.

It took a single verse for Lynn to show how skilfully she could paint a vivid picture of the mundanity and endlessly repetitive bleakness of their lives:

My daddy worked all night in the Van Lear coal mines

All day long in the field a hoin' corn

Mommy rocked the babies at night

And read the Bible by the coal oil light

And ever' thing would start all over come break of morn

Lynn remains haunted by every word of ‘Coal Miner’s Daughter’ to this day. “When I recorded that song, I didn’t care whether it hit anybody else or not. I was thinking of me.” She’d written all the lyrics and melody in 1969 – a year before recording it – originally within the bluegrass mould, a nod to her Kentucky roots.

In documenting her parents’ struggles and hardships across nine verses, she created an ‘El Paso’-length epic. Owen Bradley, her famed producer for this and many other albums, insisted she cut several verses. So out went numerous lines, including those about her mother killing a pig on “hog-killing day”; crying as she made these cuts before recording.

With top Nashville session musicians and The Jordanaires on backing vocals, the album was recorded across a series of days at Bradley's Barn in Mount Juliet, Tennessee. Apart from the title track, Loretta also wrote two more songs: ‘Any One, Any Worse, Any Where’ - a love triangle in which Lynn plays “the other woman” - and ‘What Makes Me Tick’, about her man’s infidelity; “When it comes to cheatin' honey you know every trick / I'm gonna have my head examin' and find out what makes me tick”.

Lynn’s songwriting sister Peggy Sue pitched in with ‘Another Man Loved Me Last Night’, portraying the narrator’s infidelity, as she gets no love at home and seeks it elsewhere, much like Lina in Lisa Taddeo’s classic book, Three Women – “I'd almost forgotten what love was really like / But I'm only human only a woman / I let another man love me last night”.

As Lynn said: “Those songs [were] true to life. We fought hard and we loved hard. I never knew what I was comin’ home to. I didn’t know if I was comin’ home to fightin’ or what. It was pretty rough.”

It’s almost funny how Lynn would go on to interpret the best songs from her male peers across the rest of the album, covering Glen Campbell’s ‘Less of Me’ (resisting temptation and being less judgemental); Kris Kristofferson’s ‘For The Good Times’ (keeping good memories when an affair ends); and Marty Robbins’ ‘Too Far’ (where she’s pregnant and he’s left).

It’s also interesting how she duets simply with herself on Conway Twitty’s ‘Hello Darlin’ - just weeks before she embarked on a separate career of duets with the man himself, including 10 studio albums, seven compilations, 12 hit singles, and their hit B-side, ‘You’re The Reason Our Kids Are Ugly’, which showed an aspect of their famously self-deprecating country camaraderie.

Every song on Coal Miner’s Daughter would go on to hit home with Lynn’s fans, many of whom were women much like her; living near-identical lives. Throughout her career, she refused to be fenced in, kicking down country music complacency and putting up a flag for feminism (even if she was ambivalent about the label) with her honky-tonk directness.

Infidelity, lechery, drunkenness – and even divorce – were grist to her mill. It’s telling that today, fellow Kentuckian Carly Pearce says: “Loretta Lynn is definitely the real, first, true pioneer woman to write things that maybe other women were too afraid to say.” But even back then, Lynn was breaking the mould - as fellow country legend Minnie Pearl simply put: “Loretta sang what women were thinking.”