Link copied

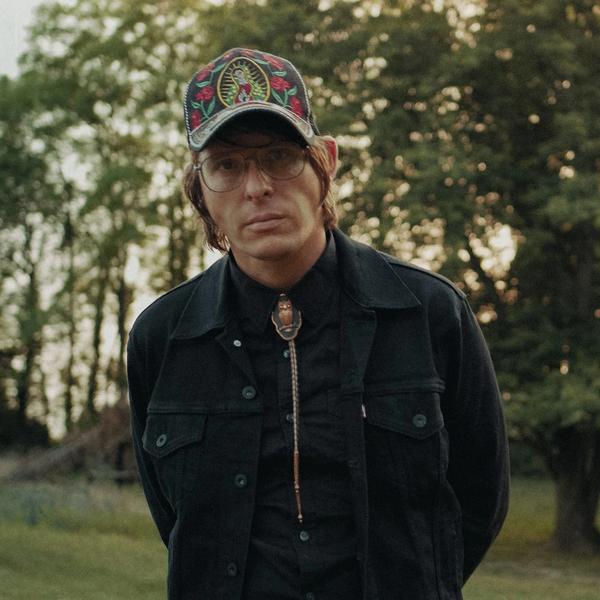

According to Stephen Wilson Jr., it’s no exaggeration to say that there isn’t a single person - himself included - who envisioned that he’d ever end up behind the microphone singing his own songs. And yet, through a series of remarkable twists and turns, he found himself practically stumbling into the spotlight.

Raised in rural Southern Indiana and currently based outside of Nashville, Wilson has channeled a rich supply of life experience - including stints as a Golden Glove boxer, a microbiologist, a guitar shredder in a rock band and a starving songwriter waiting tables to make ends meet - into his proper debut, a double album titled søn of dad.

Befitting the “Death Cab for Country” tagline he came up with to describe his style, Wilson blends the indie, country and pop influences he was brought up on into a deeply affecting brand of storytelling punctuated by his signature approach to gut-string guitar. And, after years of honing his craft, Wilson has clearly learned the art of tastefulness. In a sense, he’s been working at songwriting since before he was even aware that’s what he was doing.

It shows: søn of dad serves as a textbook example of a double album where every note counts. At times, Wilson’s songs capture the anthemic, wide-angle scope of songwriters like Springsteen, Billy Joel, and fellow Southern Indiana native John Mellencamp. On the other hand, his songs convey a wounded sensitivity as well. And even when his touch is lighter, such as when he sings about having a hole in his drywall and parking his ass on a barstool, he still manages to be moving.

Prior to the søn of dad release, Wilson sat down with Holler and walked us through the pivotal life moments that helped shape who he is as an artist, performer and person alike.

Getting into a boxing ring for the first time

I was very shy as a kid - still am, I guess. I didn’t talk much. My dad was a fighter, so he raised his two boys - me being the oldest - to be boxers as well. My brother and I were Irish twins, so we were real close in age, but were totally different. He was always very outgoing, athletic and had a big presence just like my dad. But I was this weird little introvert of a kid who couldn’t have been more different from my dad. I just looked like him and had his name.

For a lot of reasons, I got nervous really easily. My mom was around some really abusive men after she and my dad split up, so I saw a lot of domestic violence that I was keeping to myself, because I didn’t feel like I could tell my dad. There was just a lot of pent-up, nervous traumatic energy that was just always there as a kid.

I always tell people, “My first stage wasn’t a stage at all. It was a boxing ring.” So when I got into a boxing ring for the first time, that’s where I learned to perform. And I learned to watch people perform. Because my dad wasn’t just a fighter. I remember him telling me, “I’m going to put on a show for these people.” It wasn’t like, “I’m gonna knock this dude out.”

So stepping into a boxing ring, I gotta say, was probably the reason why I ever stepped onstage in the first place. I was so nervous the first time I ever performed, but being a boxer and having fought other kids growing up, and eventually fighting in the Golden Gloves as a young adult - once I did that, I could almost talk myself out of any kind of nervous fear.

It’s hard to match the intensity of fighting another human being in front of a bunch of people. I’ve got to be super grateful to my father for giving me that gift, because he didn’t really know what to do with a weirdo kid like me. I was good at school, I was a nerdy scientist and I loved music - but his contribution was for me to develop that boxing acumen, which comes in handy for all the metaphorical fights you’re going to have.

Hearing Tim McGraw’s ‘Don’t Take The Girl’

My dad raised us out in the country, so we had a really long school bus ride. It was about an hour and a half each way. The bus driver mandated that it was nothing but country music the whole time. We were poor, so I didn’t really have any way to listen to music on the bus. Honestly, I just kind of liked getting lost in the songs from the radio. One time the Tim McGraw song ‘Don’t Take the Girl’ came on.

At the time, my mom had split, and she was in these terrible relationships with abusive men. I was constantly terrified of losing her, of hearing about something terrible happening to her. That song has nothing to do with my mom’s story, but for some reason when it came on it just resonated with me on another level.

The song goes through three different storylines, and three minutes later I’m a tearful disaster on the school bus, which is not a good look for a Southern Indiana country kid. I was 11-12 years old, and I didn’t really know what the hell just happened, but I realized that I’d watched entire movies for like 90 minutes that hadn’t had an effect on me like that.

I truly felt like I’d gotten teleported. I felt like I’d just watched a whole movie go down in my mind, but the movie was also about me. I was the star and the director at the same time. That’s when I realized that songwriting was a craft. It wasn’t just like, “Oh, these guys are just sayin’ stuff while they’re playing a guitar and hoping it sounds good.” I realized, “No, this is crafted.” Just like a table or a house or a tractor.

I started to see the machinery in it, the components of the engine. That’s when I identified that I might like songs more than the average human being. I felt like they meant a lot more to me. They weren’t just sounds, or a soundtrack to my life. I started to get into really listening to the lyrics and the poetry in them.

I used to always catch my mom, when I’d see her, writing poetry on junk mail. She’d write them on the envelopes of bills she couldn’t afford to pay. She’d write hundreds and hundreds of those and just throw them away. I never understood why, but my love for lyricism and poetry became pretty intense at that age.

I started to do the same thing—secretly on my own. In my little country-ass town, that was not a good look either, to be sittin’ around writing poems. But I just couldn’t help but do it. I started reading Poe, and I got into gothic literature, Stephen King and Kurt Vonnegut. I truly became a word nerd. Even in college I would write poems and didn’t know why I was doing it. I didn’t know I was becoming a songwriter. But that moment on the bus is when I got bit by the song bug.

Discovering Soundgarden

Soundgarden taught me how to play guitar. The way I play guitar now - the open tunings, etc. - I have to give almost 100% credit to Kim Thayil and Chris Cornell from Soundgarden. I had a buddy of mine give me one of those thick Soundgarden tab books as a kid because it was just way too advanced for him. It was this old book he had lying around. That’s really how I learned guitar.

They had a real synergy of sounds that created something truly unique. It was like this underworld. Cornell was such an underrated guitar player, not just in terms of the parts he played, but also the fact that he had so many different tunings and was able to remember all those chords in those tunings and sing all those lyrics.

A lot of people just sit around and plug away on a G chord and that gets them through. There’s nothing wrong with that, but he was doing something really special, and I don’t just mean with his voice. And he was writing these enigmatic songs. ‘Limo Wreck’ and ‘Fourth of July’ are two of my favorite songs, speaking of that harmonic, perfect... I guess what you’d call synergistic dissonance happening at the same time. It was so trippy and so heavy, but so enjoyable.

I think they were real sonic visionaries, and I don’t think they quite got appreciated for that aspect. The guitar stuff they were doing, that would be fresh as hell right now. If you had some 16-year-old kids playing like that in their garage, people would lose their minds.

Seeing Willie Nelson live

I didn’t grow up listening to Willie. I grew up listening more to Johnny Cash and Hank, Sr. But I just love Willie’s reckless beauty, and the way he approaches his guitar like a songwriter, which I think is a beautiful perspective.

When you go see him in concert, it’s like he pulls the hat off the lead guitar player, puts it on his own head, does something crazy and throws it out to the crowd and then goes back to being Willie again. It’s like an 18-wheeler on the edge of a mountain. The trailer’s just hanging off the edge, and somehow he always gets it to the top without the damn thing flying down the mountain. I love that reckless-endangerment approach. He just does not care! He’s not scared one bit.

I saw him play at the Ryman one time and it changed my life. I got free tickets to it. I didn’t even know what I was in for, and I’ll never forget it. I was a seat-filler. I was 23 years old at the time living in Nashville going to school and I got a ticket just to fill a seat while wearing black for a live taping. It was insane. I’d never seen anyone play a gut-string like that. And then singing with that voice, which is just from another planet. And the way he’s able to sing with his nose.

Whenever I’d try to sing growing up, I always sang from my nose. I always got criticized for it. So when I first heard Willie sing from there as well, I was like, “Oh, he’s totally doing it and it sounds amazing.” I didn’t know at the time that I was going to sing, but I remember thinking, “If I was to ever sing, that’s how I’d do it.”

Willie Nelson, I gotta say, taught me how to sing. And he taught me a lot about guitar playing too.

A life-changing conversation with my boss

After I left my first band AutoVaughn, I hunkered down in a food-science lab in the R&D department in the Mars food company. I had a great job, married my wife, and we moved out to the country and started to raise my stepson Henry. But I just could not stop writing songs. I was writing them in the lab all the time. It seemed to be a nonstop obsession.

Because of Autovaughn, I got plugged into some songwriting rooms. Once I got into one of those rooms and realized, “Wow, people do this for a living”, I also started questioning the wizardry on the school bus. I was like, “That’s how those bastards came up with that. They get in these rooms every day.”

That was my moment when the curtain was pulled and the Wizard of Oz was revealed to me, where I could see how the levers were pulled. That’s when I realized that this was really what I wanted to do. And even though I’d been playing in this indie rock band, in the back of my mind, that seed was planted—and it was growing. So, by the time I left that band, it’s all I could think about when I was in those labs: getting in one of those writing rooms. “I want to get in a room with Tom Douglas and Craig Wiseman—with the best of the best of the best—and learn from them. I will not stop until I do.”

I had this boss who was an incredible mentor to me, and also a big fan of music. He knew where my heart was, even though he’d hired me to work there. I was moving up the corporate ladder at a pretty accelerated pace. It was a pretty scary pace, because I knew in my heart that it wasn’t where I belonged. But it was happening so fast, and it was almost too good to be true. Like, “Why would you pass this up? People would kill for this job. You’re getting opportunities that other people aren’t getting.”

So this boss pulled me aside and said, “I just want to give you a heads up that they’re grooming you for management. But I see you’re writing songs all the time. I think that’s awesome. You get your work done, but that’s all you want to do, isn’t it? If you could do anything you want, money not being an issue, what would you do?” I just told him straight-up: “Well, I’d want to be a songwriter.”

He was like, “Well, I’m just going to tell you something: they’re about to put the golden handcuffs on you. They did it to me 33 years ago, and they’re about to do it to you. You’re going to make more money than you’ve ever made. Your $60,000-a-year salary is going to be a lot more than that. You’re probably going to put your stepson in a private school, and you’re probably going to buy a better car and a better house. Before you know it, your days of getting a $20,000-a-year publishing deal and chasing down this crazy dream that I see you dreaming about all day long, that’s not going to happen. They’re going to have you handcuffed to this desk. But the handcuffs are going to be made of gold. You’re going to have more money in your bank account than you’ve ever had. But based on looking at you, you’re going to be miserable.”

It might’ve been three weeks after that conversation that I handed in my notice. I literally left the job on the basis of a metaphor that scared the living shit out of me.

Meeting Cowboy Chris

After that conversation with my boss, I met a 30-year publishing veteran from BMG named Chris Oglesby, who’s known as Cowboy Chris, the “songwriter whisperer.” He really is a songwriter cowboy. At the time, I’d met with publishers who would listen to a couple of my songs and be like, “These are real songs, man, but nobody’s gonna cut ‘em.”

Bro-country was really popular at the time, so they’d say, “The songwriting’s really good, but this isn’t party music. You need more songs about girls, beer and, preferably, trucks.” I’d be like, “I don’t really know how to write those songs,” and they’d be like, “Well, call me when you do.” And they’d pay for my lunch and then I’d never hear from them again. But then Chris heard one of my songs and brought me into this guitar pool at BMG where they pass a guitar around.

I played a couple of songs and he said, “Hey, man, I really liked your songs. I need you to come by my office tomorrow morning at 9:00 am.” I thought, “He’s going to want to tell me what I’m doing wrong, like every other publisher.” He said, “I loved those two songs you played last night.” I was expecting a ‘but,’ but instead he goes, “And I’m going to show you how serious I am about loving those songs.”

He pushed enter on his laptop and printed off a publishing deal, literally right behind him on the printer. He pulled the contract out of the printer and said, “This is a publishing deal. This is what you’ve been working for. I’m giving it to you right now because I believe in you. I think you’re the future of country music. All this bro-country bullshit is gonna be gone in five years, and you’re going to be ahead of the pack.”

He offered me a publishing deal on the spot when I couldn’t get anyone to even entertain the conversation of a deal. It wasn’t like I just signed it right then and there—we had to go through some lawyering—but he’s still my publisher to this day. He said he wanted to put me in the room with Tom Douglas and all the guys I’d dreamed of working with when I was at the labs. It was like this crazy answer to a prayer.

Chris was raised by a pastor, we had a very similar upbringing. He’s very much a man of faith—and I don’t just mean that in just the Christian sense. He’s a man of faithful decisionmaking. He has faith in people, and in things that haven’t happened yet. Like my father, he’s so good at self-actualizing - believing in something so intensely and intently that it actually comes to be true.

Having one of my songs cut by an artist for the first time

He ended up not releasing it, but the first artist to ever cut one of my songs was actually Tim McGraw. I’ll never forget it. After leaving this great job working in R&D at Mars, I’d just signed my publishing deal and I was like, “What the hell was I thinking? I’m making no money.” I was bartending and waiting tables and making nothing as a beginning songwriter. I kind of needed a sign.

This was a “God nod”, as I call it. Even though it didn’t quite pan out to be this big single, it just kind of told me that I was on the right path. For that to be my first cut, that was pretty wild, since McGraw was the artist who had started it all for me.

My dad’s passing

On September 15th, 2018—a year and a half or so after I hooked up with Chris Oglesby and signed with BMG—my dad died unexpectedly. It was the worst day of my life. I’d just gotten back from a writing trip in Texas. My dad went in for emergency surgery, so I flew to Nashville immediately. I was going to leave for Indiana the next morning and go sit with him in the hospital. The surgery went really well, and he was texting me, like “I can’t wait to see you in the morning” and stuff like that.

I was in the middle of packing clothes for a couple of nights’ stay when my sister called me in a massive panic. She said, “Dad’s dying, and I don’t know why. You have to get here as soon as possible.” I flailed around and threw some clothes in a bag. I didn’t even know what I was doing, but I sprinted out of there as fast as I could. Needless to say, I didn’t make it in time. I got into the middle of Kentucky, and I said goodbye to my dad on an iPhone 8. It wasn’t fair; it wasn’t how it was supposed to go down, but that’s the way it was gonna go down.

It was shocking how calm and cool he was about it. He wanted me to know that it was going to be okay. He’s dying and he’s like “Hey man, it’s going to be okay. Write a good song for me.” He said “I love you” four times, and then he died. My brother and my sister were there right beside him holding the phone. His voice was fading away, and by the fourth time he said “I love you,” it was like he was in a tunnel or something. Even though I wasn’t physically there, I felt his soul depart. I felt my brain re-wire in an instant.

Not only was I grieving his death in that moment, but I was grieving the death of my whole identity. I was my father’s son. That’s really all everybody knew me as back home. So it was like, “Where do I land now?” It was like grieving a double-death. Because who I was also died with him. But at the same time, a birth came with it. From his death this new reality was birthed where I sing songs for people. Because I was always so quiet, I think he would’ve been shocked, but I think it’s something he would’ve wanted me to do.

Performing 'Stand By Me' at Deadwood Songwriters Fest

A couple of weeks after my dad died, a friend of mine who runs a festival in Deadwood, South Dakota called me. He was like, “Hey man, I know your dad just died and you’re like a lost lamb in the wilderness. You should come to the Black Hills. I think it’d be really good for your soul. You need to get away from it all for a second and come here.” Against my intuition, I did it.

I’d been haunted by the Ben E. King song ‘Stand By Me’ ever since I was a kid. I don’t know why, but it’s always been one of the most haunting songs of my life. But I’d always just played around with it in the living room. But at the end of the festival, they have everybody get up and do one of their favorite covers, so I decided to play that song. There were probably a couple thousand people there, and the whole place just went crazy. I’ll never forget it.

It reminded me of a big tent revival. I can’t quite put my finger on what was happening, but it felt like my dad was a 3-year-old kid sitting on my shoulder. Suddenly, he was the kid and I was the dad—this weird reversal that didn’t make any sense to me, but also it made total sense to me. It made all the sense in the world. I felt so much peace in that moment.

That was the beginning of my career as an artist, the moment that I knew I was no longer a songwriter. It was another “God nod” - more like a God slap - like, “You’re no longer just a songwriter. You’re this.” Before my dad’s death, I don’t think I ever would’ve accepted it. I would’ve told myself, “No, I don’t do that. That’s not what I do.” But that guy died.

It was a very evident moment, and I think everyone present noticed it. And if I hadn’t noticed it, I would’ve been a fool.

søn of dad is out 15th September via Big Loud Records. For more on Stephen Wilson Jr, see below: