Link copied

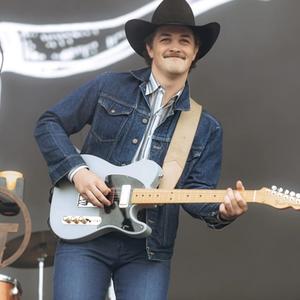

Since Zach Top arrived on the country music scene last year – crowned in a wide-brim hat upturned like his mustachioed smile – he has quickly become the genre's latest obsession. That's not necessarily just because of what he's bringing to it, but what he's bringing back.

Top and his music are reminiscent of a particular time and place, of certain artists we still look to as paragons of sound and style. That's because Top embodies something called Neo-Traditional. This once-abundant brand of country music, a style that came to define country in the 1980s and '90s, has been merely whispered throughout the genre for the last two decades.

However, now that neon-flecked songs like 'I Never Lie' and 'Bad Luck' are inescapable and Top's star is only projected to rise, Neo-Traditional is again at the forefront of country music, and everybody seems to want in.

More and more, familiar steel wails and boot-scootin’ rhythms can be heard cropping up in the music of today’s rising stars, a growing contrast to the stadium-ready country-pop productions that have dominated the genre in recent years.

Now, with the term being thrown around more frequently—and sometimes willy-nilly— we've created a guide to Neo-Traditional, breaking down the sub-genre, what it is and isn't, and how to know the difference.

What Is Neo-Traditional?

In the 1980s, mainstream country music was experiencing an identity crisis.

The genre was having a tug-of-war between the stripped-down sounds and sensibilities left over from the outlaw country movement of the 1970s and the encroaching pop that would inevitably rule at the turn of the millennium. It's not that there wasn't a happy medium at this time; there just seemed to be hardly any "country" left.

Where were the steel guitars and the fiddles, the richly composed waltzes or the ripping honky tonk numbers? Where was Hank Williams? Where was George Jones? The country music that had raised many of this decade's up-and-comers was, at this point, nearly unrecognizable, and so a return to tradition was sought. Enter Neo-Traditional.

This movement was helmed early on by George Strait, who pulled from the Western swing, Bakersfield sound, and honky tonk styles his forebears perfected, looking to greats like Williams, Jones and Merle Haggard for direction in pioneering this novel version of traditional country music.

With the 1981 release of his debut album, Strait Country, the artist reintroduced the genre to its core, reincorporating steel guitar riffs and fiddle flourishes in songs about the average Joe. It was a departure from the polished, easy-listening hits of Kenny Rogers and Eddie Rabbitt that were crossing over that same year. It was that album that would ultimately catalyze the Neo-Traditional movement, laying the groundwork for a new ol’ sound to be born.

It wasn’t long before Keith Whitley joined him. With ballads reminiscent of the old Nashville sound, he further resurrected country's more classic touches, retooling them with modernized production and more contemporary lyrics. By the mid-1980s, several more central figures would arrive to pioneer the Neo-Traditional movement. There was Patty Loveless, whose early work was heartfelt and honky tonk-fueled, and The Judds, with their down-home harmonies and earnest words.

But it was Randy Travis who would become the exemplar. His crisp and sincere baritone, paired with approachable songs like 'Forever and Ever, Amen', 'On the Other Hand' and 'Deeper Than the Holler', would come to define the style, molding it for mainstream audiences.

By this point, Neo-Traditional’s hold would be undeniable. The Judds would take home the crown for Best Country Song (‘Grandpa (Tell Me 'Bout the Good Ol' Days)’) at the 1987 Grammy Awards, with Travis earning the same honor with 'Forever and Ever, Amen’ the following year.

With Whitley's untimely death in 1989, it would be Strait and Travis who would usher Neo-Traditional country into the next decade, where an artist named Alan Jackson would pick up the torch. His hits throughout the '90s, like the ripping 'Chattahoochee' and the anthemic 'Don't Rock the Jukebox', were not only informed by traditional sounds, but they were saturated with personality - full of easy humor and a delicious simplicity and, therefore, accessible to many.

His time as one of Neo-Traditional’s heavyweights would be spent consistently gracing the Billboard Hot 100. Songs like 1999’s ‘It Must Be Love’, 2000’s ‘Where I Come From’ and ‘Drive (For Daddy Gene)’ from 2002 would all become crossover successes, earning positions in the mainstream, all-genre Top 40.

It's easy to chalk up '90s Neo-Traditionalism to a caricature of country music and its musicians. Still, the sub-genre during this decade urged country music to return to its roots and have a damn good time doing it. Acts like John Anderson, Brooks & Dunn and Joe Diffie would join Jackson, all of them adding a singular, charming kind of humanity – a swagger, a mustache and a mullet – to the traditional sensibilities Strait, Whitley and Travis had brought back to the genre.

That, however, would begin to fade as the '90s dissolved into the 2000s and pop country took the reins.

With the turn of the millennium, Strait, Travis, Jackson, Brooks & Dunn would all continue to make the music they wanted, but were steadily traded out on the charts and over the airwaves for glittery new acts with fresher, more boisterous sounds.

In 2000, Strait and Jackson even joined forces to accept such a defeat, honoring their efforts to bring tradition back to country music, releasing 'Murder On Music Row'. In the plaintive ballad, they eulogize country music, now under the thumb of pop influences and at the mercy of the almighty dollar.

"For the steel guitars no longer cry," they sing in the song, "And the fiddles barely play / But drums and rock 'n' roll guitars / Are mixed up in your face / Ole Hank wouldn't have a chance / On today's radio / Since they committed murder / Down on Music Row."

Even with this "pop" sound rising, Neo-Traditional country didn't immediately fade into outright obscurity; several newcomers like Josh Turner and Easton Corbin attempted to adhere to tradition. For years, though, pop would be the only god served.

What Isn't Neo-Traditional?

Several enduring country stars arose at the height of the Neo-Traditional movement, and it's easy to lump them all together, but they harbour marked differences.

Acts like Vince Gill, Pam Tillis, and Lorrie Morgan emerged in the late '80s. They could be associated with the Neo-Traditional style, but they existed on its fringes. Eventually, they became more at home in the approaching pop country sounds and more welcoming of its bold productions and embellished compositions. With the arrival of the 1990s, though, a more distinct line would be drawn, delineating what was Neo-Traditional and what was country pop.

This new decade would welcome the rise of Garth Brooks, Toby Keith and John Michael Montgomery and even ushered in a new era for Reba McEntire. They all came onto the scene fitted with an undeniable country backbone, but by infusing pop and rock into their sound, relying on easy hooks and simple melodies, their music earned them cushy crossover appeal. And while '90s acts like Lonestar and Martina McBride began their careers with a Neo-Traditionalist bent, they, too, would bend to the pull of pop.

Of those acts, Brooks, significantly, would help to guide country into its pop age, his music fully embracing those pop and rock influences that Neo-Traditionalism had attempted to combat.

So What Is Neo-Traditional Today?

As mentioned before, Neo-Traditional country didn't cease to exist with the rise of pop country. It just became much more challenging to be heard against the increasingly steady flow of 808 beats and rock riffs assailing the charts and airwaves.

In the early 2000s, more traditionally inclined artists like Joe Nichols and Craig Morgan would join Turner and Corbin in a half-hearted crusade to carry on certain country customs. Only with the arrival of acts like Cody Jinks and, especially, Midland, did Neo-Traditional country formally take shape for the 21st century listener.

Midland's swoon-worthy harmonies and steel-soaked arrangements infused Strait influences with their glittering California coast and sweeping high desert sounds, making reminiscent yet fresh, worn-in but brand-new music. When the trio came onto the scene in 2014, their music wasn't by-the-book Neo-Traditional, but it was the closest thing to it in what felt like a very long while.

That is until recently with the ascent of Zach Top, who is Neo-Traditional to a tee; a near-sonic copy of his forebears, for better or worse. He came to the genre armed with a Whitley croon, a Jackson-esque charm and a Travis-tinged sincerity that makes his music as irresistible as his heroes. Flanked closely by the swaggering Drake Milligan, the unflappable Jake Worthington and the soulful Randall King, Top has encouraged popularity back to the style, leading the charge like George Strait did before him. Many more are bound to follow. But why now?

Country music, like many things, is cyclical, and the genre was bound to make its way back here. Today, it is at a crossroads, once again finding itself in the midst of an identity crisis. Now, on the other side of the 2010s bro-country boom and in the middle of a prolonged period of oversaturated and overproduced pop country, perhaps country music is attempting to rediscover its traditions and, in turn, unearth its roots once more.

For more on 80s and 90s Neo-Traditional Country, see below: