Link copied

Gretchen Peters is awash with emotion. The beloved singer-songwriter has just completed her penultimate UK tour – making her final appearance at King’s Place, London alongside her band.

After decades of being on the road and much soul searching, this summer Peters announced that it was time to say farewell to touring.

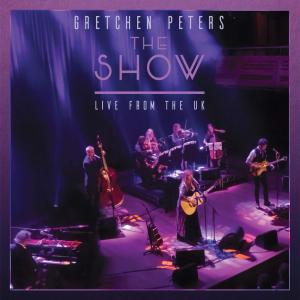

Perhaps ironically, Peters’ latest record is a double live album, recorded around the UK in 2019 with her band and a brilliant, all-female, Scottish string quartet. But she hadn’t consciously planned to quit touring when working on The Show: Live from the UK, which was released just days before her farewell statement in August 2022.

She had, however, already been musing on what life might look like if she stopped touring. She asked herself: “Who am I if I’m not doing this? Because it’s been such a huge part of my identity for a long time.”

So proud were they of these epic 2019 live concerts that Peters knew she had to document them. Then they came off the road, got home, did a few more gigs, and she began to feel the effects of burnout.

“I’d done all this thinking, ruminating and soul-searching earlier about what life was going to look like when I wouldn’t be able to do this for a living. Then the pandemic hit and said: would you like a preview? Because here it is!”

At the same time she started mixing the live album tracks and feeling an incredible energy in the room. “I was hearing the sound of the audience, in stark relief to what we were dealing with at that point, which was lockdown and doing maybe a live stream where all you get is a few little hearts floating up on your screen.”

“It brought me to tears, the sound of that room and those people and the energy that they give you. It all just really hit home. I worked through my feelings of grief and fear and all kinds of things that are not particularly pleasant in looking at stopping.”

Good news for Gretchen Peters fans is that she’s going to continue to write songs, release albums and maybe appear at the odd festival or one-off gig. But the big tours are definitely over. And she is very much over the cycle of: write this album, make this album, release it, promote it, tour it – then immediately get asked: ‘have you written anything, when is your next album coming out?’

“I willingly got on that hamster wheel and didn’t get off for 15, 20 years,” she says “That’s where the burnout was coming in. I started to ask myself, why is the next step to make another album? And how long do I do this? So that was the biggest contributor to it, this feeling that the cycle just goes on and on.”

Peters also observes how much the music business has changed. “It seems like the life cycle of an album is about two weeks, then everybody forgets it. People’s attention spans are so short.”

She started to ask herself if she really wanted to go through two years of extreme hard work for what she created to have a two-week life cycle. “I know my albums haven’t been like that for the people – thank god – who love them and play them. I feel for new and young artists. You used to know you were touring to promote the sale of the album, now it’s the other way around.”

Loop back to 1988 and Gretchen Peters moved to Nashville to ply her trade. Born in Bronxville, New York and raised in Boulder, Colorado, she was initially known as a songwriter, building up a portfolio of carefully-crafted compositions – resembling short stories – that have been recorded by everyone from Shania Twain and Kenny Rogers to Randy Travis and Etta James.

She was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2014, and her other awards include the 1995 CMA Song of the Year for Martina McBride’s recording of ‘Independence Day’, the 2015 Americana Music Association UK International Album of the Year for Blackbirds, plus the 2021 Poets Award from the ACM.

We spoke to her about her artistic evolution, Nashville throughout the decades, being embraced by the UK and the homogenisation of country radio. We also discussed how being an ally and mother to a transgender son – particularly in the eye of the media – has solidified her world view.

What did you expect when you arrived in Nashville in the 1980s – and how did the reality differ?

I’m not sure what I expected. I was eager to dive into the whole thing; to be with my peers and people trying to do what I was trying to do. The thing that perplexed me the most was this delineation between artists and songwriters – that you were either one or the other.

Having grown up with Joni Mitchell and Paul Simon, Bob Dylan and Gram Parsons, I couldn’t understand why every door that I knocked on, behind that door was someone asking me: did I want to be a songwriter or did I want to be an artist? I couldn’t figure that out.

So the States pigeonholed you as a songwriter, but did the warm response in the UK change your mind?

Yes, that was a huge motivation to keep coming back to the UK. For more than a decade I was put in the songwriter box in the US and even referred to in the press sometimes as ‘Nashville songwriter who decided she wanted to become an artist’ - which is not at all what happened. I moved to Nashville because I wanted to do all of those things. I wanted to write, make records, tour and do all of it. I saw it as one thing.

So a lot of the reason I felt so free and unencumbered and able to just be myself in the UK is because I was embraced as a singer-songwriter with no effort to keep me in this box. I’ve fought that on this side of the pond for a long time; about 10 years ago I threw off that identity, but it followed me around for a long time.

Were you given any rubbish advice at the beginning? Maybe some good advice too?

The one thing I was very much encouraged by a lot of people to do was co-write – which turned out to be something I was constitutionally not fit for – with a few exceptions. I tried so hard to be one of those songwriters who co-writes with lots of different people, and it’s always felt incredibly awkward and inhibiting to me.

Conversely the great piece of advice that I got from my own publisher early on was ‘quit trying to co-write! I like what you write by yourself better.’ So every bad piece of advice, thank god, was countered with a good one.

The other thing is tied into my bewilderment – back to the division of duties, singer versus songwriter thing – on my very first round of door-knocking and sidewalk-pounding trying to find publishers. Being asked over and over again, “Do you want to be a singer or do you want to be a songwriter?” I think that was short-sighted, I don’t think that was good advice.

On some levels it’s a machine here, and you have to be a proper machine part, you have to fit into the slot of the machine for them to know what to do with you.

So how much control did you have?

I was young and bull-headed enough to know inside myself – on some level – that I was not going to listen to those people. I don’t know what that is inside of you when you’re in your twenties and say you know everything. But I know who I am and this is what I’m going to do!

Did you have anyone else to turn to?

Yes, I had mentors, people who saw me and what I was going to do, which is to me a mind-blowing talent. How does anybody look at a young, unformed person and say you haven’t done it yet, but I know what you’re going to do? I had those kind of mentors – publishers and producers – saying hold fast, do your thing.

Harlan Howard was a huge mentor; he took a shine to me and we started going out to lunch. It wasn’t that he particularly imparted a lot of advice, but just being able to be around him and see somebody who had weathered decades of being a songwriter in Nashville.

How has Nashville changed since – for the better and the worse?

One way I think it’s changed for the better, when I was starting out as a recording artist, and even as a songwriter, there was this idea that a song had one shot. If it didn’t do well, that song is burned. It’s damaged goods, it’s over, you could never get that song recorded.

Now I think recording artists – and this is very strongly in the folk music tradition where I come from – know that a great song is a great song is a great song. They’ll record a song over that’s been recorded five years ago; there’s no sense of ‘I’m not going to touch that because so and so recorded it’. I love that there’s that sort of freedom.

One thing that’s definitely changed for the worse: I used to believe in the 80s and 90s that a great song will win out and find its place. It will climb up through all kinds of obstacles because it’s great, and greatness gets rewarded. But I don’t believe that’s true any more. I think it’s largely up to the gatekeepers.

So has the industry improved – or gone backwards – especially for women? Is it still hard to get your song played?

I think it’s as hard, maybe even harder for a brand-new recording artist. I was told on my first radio tour that ‘we only play one or two women an hour. That’s it. Sorry… and we already have Reba and Shania.’ Basically they were saying: no chance. It’s largely the same way now.

When I was starting out, the gatekeepers of radio were the consultants. We were coming out of an era when radio was more local; if a DJ or programme director in Abilene loved a record they’d play it. The idea that the songs you would hear in Abilene, Texas and those you’d hear in Macon, Georgia would be the same was brand new. When I was coming round as a new artist they consolidated that into a consortium of consultants across all the commercial radio stations, and to me that really damaged the radio stations. That was the beginning of a great homogenisation, and the beginning of the end.

If you look at the songs in the 90s that you still hear on the radio today, ‘Independence Day’ is one of them, ‘Strawberry Wine’ is another. Those songs have so many strikes against them in logic, in terms of radio programming. ‘Strawberry Wine’ is five minutes long, a slow waltz, done by female artist (Deana Carter). ‘Independence Day’ is a dark story, also by a female artist (Martina McBride), and yet those are the songs that tend to break through and become a memorable part of country music.

It’s like Steve Earle said: you have to remember that country radio isn’t selling music, it’s selling tyres. They have a job to do and it’s not to promote great songs, it’s to keep people dialled into that radio so those ads can be heard. The recording industry turned over the reins to these consultants and ‘kowtowed’ to them to the extent that we really damaged the music. And I don’t think it’s recovered.

The good news is I think the great songs haven’t gone away, they just tend to be called Americana now! Being a born misfit, I welcome it.

Your career turning point must have been writing ‘Independence Day’?

That’s definitely when the rockets kicked in. Before ‘Independence Day’ I wrote by myself and had some hits like ‘Let That Pony Ride’ by Pam Tillis, and a couple more Martina McBride songs. So people started to know my name – when there’s only one name beside a song title people tend to notice, but if there are two or three names it’s a little murkier what you’re responsible for. ‘Independence Day’ kicked it into high gear for us, for sure.

I wonder if it’s really righteous anger that propels you?

It’s only possible to do this after you’ve been doing it for quite a while, but if I look at the threads that run through my songs, I think writers have wounds they pick at; certain things they keep going back to. For me, there seems to be this thread of people that are trapped, people in difficult situations, and how they try to get out of them or deal with them or think about them or experience them. I don’t know why that is, but every writer has their well they go back to.

A lot of these people are powerless and their powerlessness makes me angry. Because the world is the way it is, a lot of those people are women or children, so it’s not an accident that a lot of the protagonists in my songs are children – like the little girl in ‘Independence Day’ or the child in ‘Idlewild’. Or women, because they tend to be powerless in our culture. I think righteous anger is a pretty good way to put it; that’s fuel for me as a writer.

How has being a trans ally and mother to a transgender son shaped you and your world view? And are you surprised by media figures, including some feminists, who attack the trans community – or can you ignore it?

I find it baffling as a feminist. The first issue of Ms magazine coincided with when I came of age at 12 or 13 years old, so I can’t get my head around this idea that it’s a feminist idea to be anti-trans. There’s many levels on which I can’t get my head around it.

First of all, I’m the mother of a trans-man and I know exactly what he went through in his childhood; the only person who knows better is him. I also know that all he ever wanted to do was to be able to live his life as himself. So this whole idea that there’s some sort of agenda to corrupt the youth, I don’t even know what the agenda is supposed to be. But it’s complete bullshit. He doesn’t even want to be known for that, he just wants to live a normal, average life. I know that because I know him.

As a mother I just can’t with these people. My son was suicidal; most trans-kids are at some point. I know how devastating and dangerous it can be in any case, but especially without someone in your life who receives you for who you are and supports you and wants you to be happy and understands and is accepting… and I even hate the word ‘accepting’ because who are we to accept? We should accept everybody, we should accept who they say they are.

But as a mother that’s a bell you can never ever un-ring. And for people from the outside to tell parents of trans-kids that they’re doing harm to their kids is just the most presumptuous, horrific, abusive thing that I can imagine. Unless you have stood in those parents’ shoes, shut up.

It’s strange how trans people have been vilified by ‘religious’ people, who should theoretically embrace everyone.

They’ve gotten very far away from Jesus, that’s all I can say. The people that Jesus would berate if he came back would be the people that claim to follow him… for the most part. I know some Christians who really try to be Christ-like, but they’re unfortunately far out-shouted by the militant Christian types. It’s the same old story. Transgender people are just the new ‘other’… there’s always an ‘other’. People like this just use the ‘other’ to invoke fear. It’s human nature; that’s what we do.

---

Gretchen Peters' 2022 record, The Show: Live from the UK, is out now. Read our full review here.