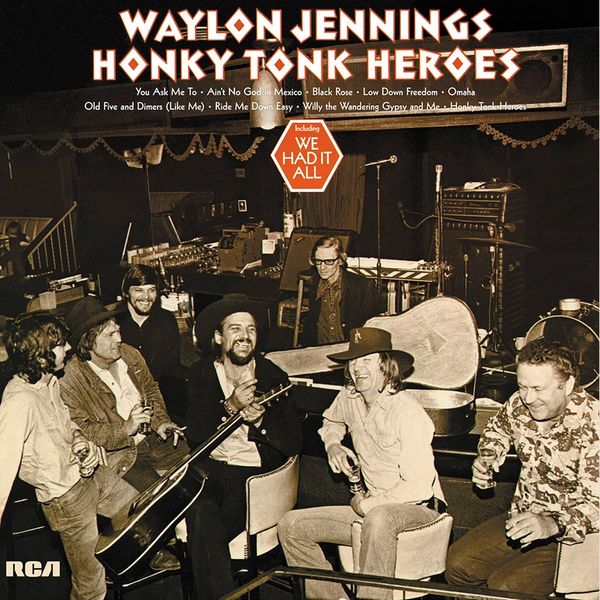

Waylon Jennings - Honky Tonk Heroes

By Jof Owen

Honky Tonk Heroes ended up being the first real outlaw country record, and to many it remains Waylon Jennings' finest moment.

Link copied

“Waylon Jennings and Billy Joe Shaver are the first of the last real cowboys”, begin the sleeve notes to Honky Tonk Heroes. “It isn’t easy being a cowboy in this day and time, but Waylon and Billy Joe get it done.”

The early 70s were a tumultuous time for country music. Waylon Jennings, seemingly in an endless war with his label RCA - label heads Chet Atkins and Owen Bradley and their Nashville Sound - was tired of the restrictions of the Nashville studio system. By 1972 that battle was coming to a messy head. Jennings was looking for autonomy in the studio, he fought for the right to use his own musicians and to take his time over the recording sessions, preferring to work on his own clock with his touring band The Waylors.

As legend has it, the seeds of Honky Tonk Heroes were first sown in March 1972 in Austin, Texas, at the Dripping Springs Reunion music festival - nearly a year before the album was eventually made in February of 1973. Texan singer and songwriter Billy Joe Shaver was only just starting out in Nashville when he took the trip back down to Austin with one Kris Kristofferson. Jennings had already recorded one of Shaver’s songs, ‘Low Down Freedom’ - and he’d go on to cut another, ‘Black Rose’, in May of that year - but neither of the songs had made it onto a record.

When Jennings was backstage at the festival that weekend, where he was appearing as one of the headliners, he heard Shaver singing a song he’d written, ‘Willy The Wandering Gypsy And Me’. Upon asking him if he had any more songs like it, Shaver told him he had “a whole stack of them”, it was there Jennings invited him to Nashville to record an album.

At the time, Billy Joe Shaver was having about as much luck as Jennings. A few months, countless calls and messages later, Shaver still hadn’t heard anything back from him. He’d been chasing Jennings around Nashville - trying to get him to make good on that promise he made at Dripping Springs - but got the feeling he was being brushed off. He eventually caught up with him at a recording session at RCA’s Studio A and waited patiently outside for him to come out.

When Jennings sent his right-hand man - Roger "Captain Midnight" Schutt - out to him with a hundred-dollar bill for him to go away, Shaver had had enough. He refused the money and pushed past Schutt into the studio where he confronted Jennings – in front of all the “girls and bikers and all kinds of hangers-on” that he had around him at that time - and told him he was willing to fight him if he didn’t listen to his songs. Jennings told him he could play him one song at a time, if he liked it then Shaver could play him another.

Three songs later, Jennings stopped him and told him he’d record every one of them and finally make a whole album of his songs.

Nine of Shaver’s songs make up the 10-track album, along with the Donnie Fritts and Troy Seals song ‘We Had It All’, tagged onto the end as a more “conventional” single at the insistence of RCA. Jennings had brought in Neil Reshen, a hard-nosed New York attorney, to deal with the label - and after months of negotiations he secured a new contract with them, guaranteeing his artistic freedom in the studio. It was unprecedented in Nashville at the time, paving the way for other artists and signalling the decline of not only the studio system but the Nashville Sound.

Honky Town Heroes was recorded back at RCA Studio A, with production split between Jennings, Tompall Glaser and Ronny Light. It sounded like nothing else that was coming out of Nashville at the time, Waylon doubling down on the stripped-back, raw country sound that his previous album, Lonesome, On’ry And Mean, had only hinted at. Gritty and loose, but with a tight swamp-rock rhythm section that blended with the barroom rock n roll swagger that Jennings had become synonymous with, it sounded like a late-night jam session, capturing the rowdy live shows that Waylon and his band were known for.

"They possessed a poetic and mythic masculinity that looked back to the American Old West"

The songs were all “new cowboy songs”, Jennings set on reinventing himself and his group of misfits and malcontents as “jet-age cowboys” - the progenitors of the outlaw country movement. They possessed a poetic and mythic masculinity that looked back to the American Old West, to saloon brawls, gunslingers defending the underdog and fighting against social injustice, all mixed in with the hippy counterculture ethos of the late-60s and the Beats.

The record reimagined Waylon et al as the “lovable losers”, the anti-heroes of Nashville, rambling, gambling and strung out on amphetamines at their late-night pinball sessions at Burger Boy. They were thumbing lifts on the open highway with a defiant, restless longing for the freedom of the road, dreaming of a mythic place where “the woman folks are friendly and the law leaves you alone”.

As Jennings recalled in his autobiography, “Billy Joe talked the way a modern cowboy would speak if he stepped out of the West and lived today. He had command of Texas lingo, his world was as down to earth and real as the day is long, and he wore his Lone Star birth-right like a badge.”

"Honky Tonk Heroes ended up being the first real outlaw country record, and to many it remains Waylon Jennings' finest moment"

Honky Tonk Heroes ended up being the first real outlaw country record, and to many it remains Waylon Jennings' finest moment. Country music wouldn’t be where it is and sound like it does today if it wasn’t for this record - it changed the course that country music took forever. Its influence has continued to echo down through the last 50 years and can still be heard in everyone who dares to step outside of the lines, while retaining and holding true to a traditionalism that sits at the very heart of the music itself.

What at the time seemed to be just one small step for Waylon Jennings, ended up being one giant leap for the genre - modern outlaw artists from Chris Stapleton to Sturgill Simpson, Margo Price to Jaime Wyatt, are indebted to the first few steps that Jennings and Shaver took all those years ago.

When Billy Joe Shaver, the man who Willie Nelson had described as “the greatest living songwriter”, died this year at the age of 81 - country music lost one of its truest originals and innovators. The songs he wrote are more than just cowboy songs. They’re national anthems.

Check out Waylon Jennings' songs on the playlists below: