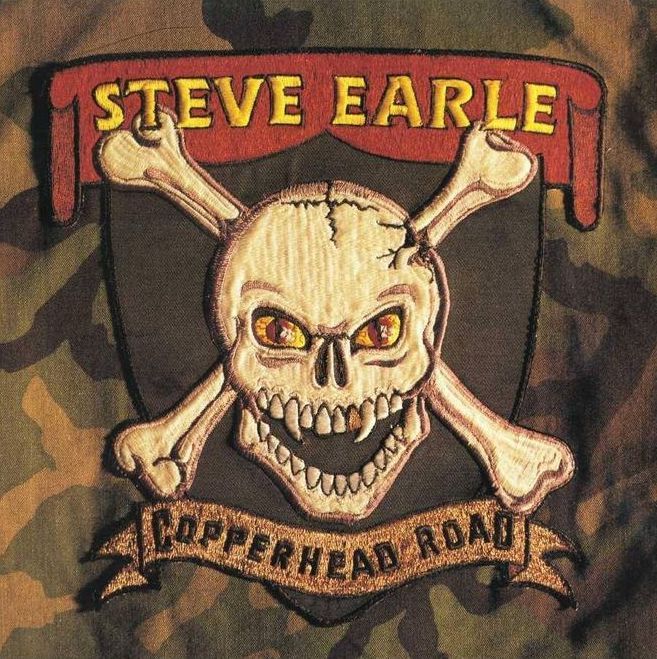

Uni Records | 1988

After working within a standard country template for his first two albums, Steve Earle embraced hard rock with his third effort Copperhead Road, kicking off the doggedly nonconformist streak that’s defined his career ever since.

Link copied

In late 1987, Steve Earle decided it was time for a change. After starting his career with a pair of albums marketed to a country audience, the Texas-bred singer-songwriter, who’d been based in Nashville for almost a decade and a half at that point, felt like the writing was on the wall.

Sure, his sophomore effort Exit 0 (released earlier the same year) had earned him two Grammy nominations, but Earle could sense that he was barking up the wrong tree by courting country radio. Alas, he was about to take a page from “outlaw country” icons Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson by pursuing creative freedom over marketability.

As fate would have it, Earle crashed an industry party for the re-launch of the Uni label, a subsidiary of MCA (with whom Earle was under contract at the time). At the party, Earle let it be known to then-MCA head Irving Azoff and then-Uni president David Simone that he wanted to join Uni’s roster.

The two execs informed him that Uni wasn’t an appropriate platform for country acts, given that the label had been reconfigured as a clearinghouse for cutting-edge hip hop and pop/rock artists like Eric B. & Rakim, Swans and Frankie Goes To Hollywood. Undeterred, Earle replied: “Then I’ll make a rock and roll record.

On completion of that record, his third full-length effort Copperhead Road, Earle would hype his new direction by describing it as “the world’s first hybrid of heavy metal and bluegrass.” Perhaps he actually believed himself when he put it that way, but Copperhead Road doesn’t quite come across as the radical turn into uncharted waters that Earle wanted the world to expect.

“Copperhead Road oozed an attitude that shared more in common with the hard-charging, era-defining sound of Guns N’ Roses and Van Halen than with bluegrass”

By all accounts, it didn’t land that way in 1988, and it certainly doesn’t land that way now. At times, such as when cottony-soft synths and thundering tom toms take center stage on the love song ‘Waiting on You’, Earle wades neck-deep into slick “power ballad” territory, as if aiming for the same tone and feel of smash hits like Whitsnake’s ‘Is This Love,’ Aerosmith’s ‘Angel’ and Cheap Trick’s ‘The Flame’—songs that became synonymous with slow dancing and arenas lit up by endless rows of lighters.

Nevertheless, Copperhead Road oozed an attitude that shared more in common with the hard-charging, era-defining sound of Guns N’ Roses and Van Halen than with bluegrass. Of course, the gated, artificial reverb on the snare drum just screams “1980s” - the album was recorded onto digital tape, after all, by Joe Hardy, the same engineer responsible for ZZ Top’s Afterburner.

Still, if you look past the dated production values, Copperhead Road captures hints of the seething power Earle and his band The Dukes would come to be known for in their live show. Additionally, Earle did at the very least point the way to the fact that country and rock were ripe for fresh new combinations, so long as one dared to step out on a limb and try them.

On ‘Back to the Wall,’ for example, the entire band holds back as an electric guitar chord rings out, flickering like a low flame casting shadows on a wall in an otherwise darkened room. The chord immediately recalls bluesy, Bon Scott-period AC/DC tunes like ‘Down Payment Blues.’

But when all the instruments build up to a full roar over an insistent, meat-and-potatoes chorus riff that would have made Beavis and Butt-head stand up and sing along, Earle and The Dukes arrive at the missing link between AC/DC’s Malcolm Young and Rich Robinson of The Black Crowes, whose debut album would arrive three months after Copperhead Road.

It’s also hard to imagine a band like Junkyard coming up with their combination of gutter-glam metal and drawling Southern rock without an artist like Earle to pave the way. (Earle would later work with Junkyard on a handful of songs for their 1991 sophomore album Sixes, Sevens and Nines.)

Earle certainly did crank up the amplifiers on the tunes ’Back to the Wall,’ ‘Once You Love’ and, in particular, the title track, which aspiries to the same intensity that Neil Young marshalled when his band Crazy Horse were at their most gripping.

Meanwhile, Celtic rabble rousers The Pogues fill-in as the backing band on ‘Johnny Come Lately,’ which is sung from the point of view of a Vietnam veteran who compares his grandfather’s rose-tinted WWII stories to his own military experience.

On several of the tracks, the celebratory barroom-stomping quality of the music runs counter to the seriousness of the subject matter. Conversely, Earle hadn’t yet reached the point where he was comfortable issuing didactic screeds on subjects like patriotism and immigration.

In that regard, Copperhead Road benefits from the undercurrent of whimsy that offsets his observations about Wall Street, homelessness, Reagan, America’s war on drugs, the draft that hung over everyone of age to serve in Vietnam, etc.

For ‘Copperhead Road,’ for example, Earle drew inspiration from a news story he heard in 1975 - a year or so after he’d moved to Nashville and, crucially, just as the Vietnam war was finally drawing to a close. In both the song and real life, a veteran from a family of bootleggers returns to the States to start a large-scale marijuana operation before the government intervenes.

“Now the D.E.A’s got a chopper in the air,” Earle sings, “I wake up screaming like I’m back over there.” Ominously, he adds, “I learned a thing or two from Charlie, don’t you know? / You’d better stay away from Copperhead Road”—hinting at a violent confrontation between the two parties.

The anthemic disposition of the music, however, partially conceals Earle’s stance and positions him as an impartial narrator, a voice that leaves more room for the listener to sit with the songs for a while before eventually catching-on to what Earle is trying to communicate.

‘Back to the Wall’ initially presents itself as a first-person reflection on minor success (and the way fame colors friendships)—until you realize that Earle has cleverly placed the song’s secondary message in the foreground and vice-versa.

Earle would soon adopt a far more pointed and overtly left-leaning lyrical approach, but his somewhat removed perspective on Copperhead Road allows him to draw coherent connections between the socio-political and the personal. In fact, the album reminds us that not only can love songs and politics go together, but that artists need both if they want to avoid becoming one-dimensional.

Over the years, Earle has proven that he can be just as “heavy” wielding acoustic instruments as when he’s fronting a rock band blaring away at full bore. Copperhead Road marks the first glimpses of the contrasts that would come to define his work, not to mention the doggedly nonconformist bent that has guided his career ever since.

He may have been stretching the truth a bit by hawking Copperhead Road as a metal-bluegrass fusion, but what’s still undeniable is that the album marks the first step onto a path of his own making.

7.5/10

Copperhead Road was released in 1988 via Uni Records

You can purchase the record from Holler's selected partners below:

Uni Records | 1988

Items featured on Holler are first selected by our editorial team and then made available to buy. When you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

For more on Justin Townes Earle, see below:

For more on Steve Earle, see below: