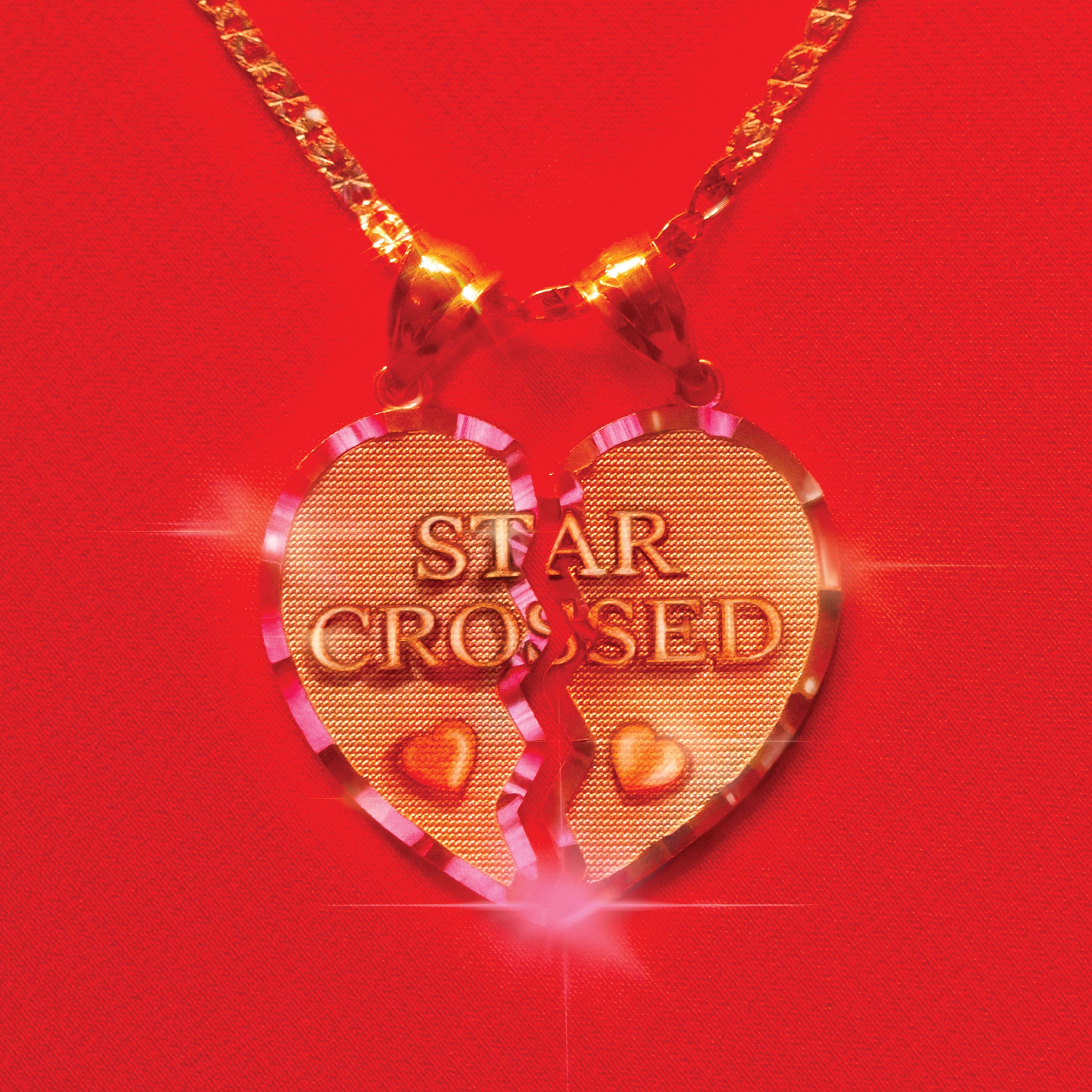

Interscope / MCA | 2021

By Amanda Wicks

On star-crossed, Musgraves' vulnerability doesn’t fully disappear, but neither does she trust it so completely anymore. What emerges are astute observations told plainly. Wrapping them in witticisms or metaphors would lose the truth they need to convey — to herself as much as to anyone else.

Link copied

When news broke in July 2020 that Kacey Musgraves had filed for divorce from husband and fellow singer/songwriter Ruston Kelly, after two and a half years of marriage, it seemed like only a matter of time before one of the most lyrically sharp-witted songwriters in recent years penned her way out of the wreckage.

Musgraves’ 2018 album Golden Hour had explored the radiant glow of love. It was feeling right down the line, she told NPR at the time. On lead single ‘Butterflies’, a song Musgraves said she wrote three weeks after meeting Kelly, she sang with a kind of hazy delight. “I was all in,” she said. “I was like, ‘This is my person’”.

If Golden Hour was a fairytale, Musgraves’ follow-up star-crossed is a tragedy — a structure she teased in a series of conversations leading up to its release. But the sense of loss looming over the release is as much about who she is in the wake of so many shattered dreams as it is over the dissolution of her marriage. Musgraves lost herself somewhere in the tangle of losing Kelly, and star-crossed, in part, follows the process of working back to herself.

The first half of the album finds her stumbling to gain clarity over the relationship’s breakdown and who she’s become in the aftermath. Her musical choices reflect that searching, reaching grasp - ping-ponging from style to style rather than building in any cohesive direction.

Given that Golden Hour played with pop touches, the question was whether its follow-up would serve as the crossover moment that many female country artists — Faith Hill, Taylor Swift — have attempted in their careers. ‘good wife’ and ‘cherry blossom’ sit more squarely in pop than any of Musgraves’ previous work; the former uses autotune to highlight Musgraves’ disconnect from the part she’s been asked to play, but the effect goes too far and overshadows her modest, reedy voice.

While that experimentation is nothing new for Musgraves, the new forms and sounds which make their way onto the first half of the album feel detached from the storytelling and lyricism upon which she’s built her career. The production doesn’t bolster the songs — it buries them.

Interestingly, most of the album’s early songs, the ones that venture in new, disjointed musical directions, revolve around fantasy and escape — wishing to be a good wife, to go back to simpler times and to regain her lost love as though she were a damsel on the silver screen. Musgraves’ confidence has shattered, and the songs look for ways to make sense of those pieces.

She finds her footing when she moves away from fantasy and back into reality. Some of the album’s best songs appear on the latter half where she does more reflecting — and feeling — than imagining.

Listen to how ‘breadwinner’ follows Golden Hour’s ‘Butterflies’. Musgraves once thrilled at finding a partner who went about “Stealin’ my heart, ‘stead of stealin’ my crown”, but that dream morphs into a harsher truth. “He wants a breadwinner / He wants your dinner until he ain’t hungry anymore / He wants your shimmer to make him feel bigger until he starts feeling insecure”, she sings with an undercurrent of resentment on the chorus. It’s as close as she gets to scorned.

Two of the softer songs, ‘hookup scene’ and ‘camera roll’, exemplify why Musgraves has risen to become such a celebrated songwriter. On the former, against a quietly plucked guitar, she sings about trying to move on, only to realize that what she had perhaps wasn’t so bad. Having got out, her choices suddenly seem hazy; the song ricochets with doubt.

‘camera roll’ serves as a smartphone-ode to the ways in which the past constantly lingers over the present. Guitar and carousel-like synths build a soft glow in the background, enlarging the singer/songwriter type of music she created across her first two albums and building on the musical stretching she did on Golden Hour. “Chronological order ain’t nothing but torture / Scroll too far back, that’s what you get”, she sings plaintively.

Musgraves chose to end star-crossed with a cover of Argentinian singer Mercedes Sosa’s song of gratitude, ‘Gracias a La Vida’. Over the course of the track, Musgraves’ voice shifts into a warped autotune, suggesting she’s not fully through the tragedy of this particular moment. Gratitude, insofar as it requires accepting both the pleasure and pain of any experience, is too hard to swallow just yet.

Over three albums, Musgraves has deployed an acerbic wit. But wit builds a wall — it’s a kind of armor that guards the vulnerable from bigger truths. Golden Hour saw Musgraves soften, lean into life’s more precious moments with tender-hearted awe. On star-crossed, that vulnerability doesn’t fully disappear, but neither does she trust it so completely anymore. What emerges are astute observations told plainly. Wrapping them in witticisms or metaphors would lose the truth they need to convey — to herself as much as to anyone else.

7.5 / 10

You can purchase star crossed from Holler's selected partners below:

Interscope / MCA | 2021

Items featured on Holler are first selected by our editorial team and then made available to buy. When you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Read Holler’s round-up of The Best Kacey Musgraves Songs.