Link copied

To modern ears, bluegrass might seem like an eternally safe space for close harmonies, gentle, collaborative musicianship and everyone uniting to preserve tradition – almost a nostalgia for nostalgia itself. But initially, the reality was somewhat different, and by the time the very first bluegrass festival took place on July 4th 1961, it was all-out war.

As a musical genre that had only been invented two decades earlier by “the father of bluegrass” Bill Monroe, it was still on the periphery for many earnest fans of folk music (seen as the nerdy brother of country) and faced fresh assault from the new sensation of rock & roll. Having even one bluegrass band at a folk festival could get a mixed reaction from folk purists; having any more would be a huge gamble. Yet one man was bold enough to put his money where his mouth was: singer and recording artist, Bill Clifton. And history was made.

Like many musicians, Clifton also had a day job as a sales broker and stockbroker. He really knew his music, though, and compiled one of the first comprehensive bluegrass songbooks - his first in 1951 even containing a foreword by Woody Guthrie. From this, he was hired as a producer for the outdoor venue of Oak Leaf Park in Luray, Virginia. From May through September he snagged every bluegrass act around, calculating there was an audience to make every Sunday special.

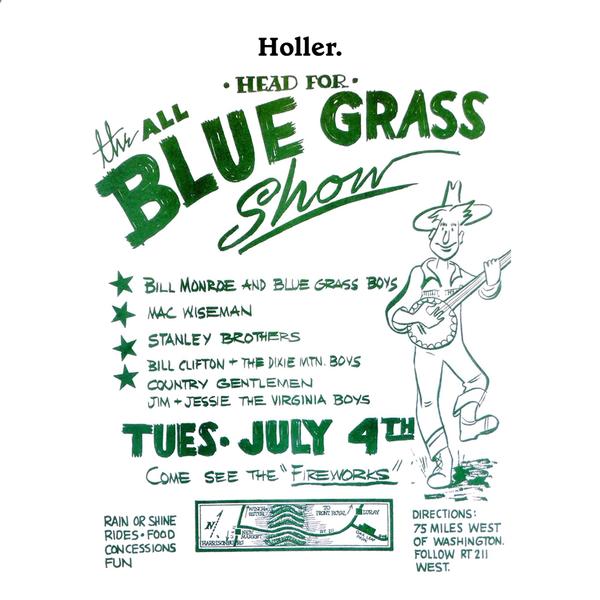

But for July 4th 1961, he decided to book an entire bluegrass line-up for an all-day festival, changing bluegrass history forever. The very first event to use the term ‘bluegrass festival’, many must have thought Clifton was nuts - nobody in their right mind ever programmed bluegrass acts across a whole day. But when 2,200 people attended the show – mainly from the D.C., Baltimore, Northern Virginia region, but also from as far away as New York City and Boston – it opened up a new platform for bluegrass music; a route out of potential obscurity and dwindling relevance.

On the bill were some of the most exciting acts of the era: Washington's hot new progressive bluegrass band, the Country Gentlemen; Jim and Jesse aka the McReynolds brothers from Virginia; fellow Virginian Mac Wiseman (who was also co-founder of the CMA); and the festival host himself with his own band, the Dixie Mountain Boys.

"The Father of Bluegrass" Bill Monroe

But big trouble was brewing from the huge headline acts and their egos: the Stanley Brothers – Carter and Ralph; and “the father of bluegrass” Bill Monroe. Clifton had also initially wanted two more of popular acts: Flatt and Scruggs, and Reno and Smiley. But the latter duo’s manager, Carlton Haney, wouldn’t lower their fee from $500. Flatt and Scruggs simply refused to appear on the same stage as Monroe, let alone the Stanley Brothers. Professional grievances were simmering away - for even though fans just loved the crossovers of styles and material in all the bluegrass outfits, the acts themselves resented anyone parking their tanks on their particular bit of lawn.

To these artists, identity and uniqueness was everything. Imitation was not the sincerest form of flattery (even if Elvis Presley had recorded a cover of Monroe’s ‘Blue Moon Of Kentucky’ as the B-side of his debut single, ‘That’s All Right’). Monroe proudly boasted: “Bluegrass is wonderful music. I'm glad I originated it,” and pointedly said, “I was determined to carve out a music of my own. I didn't want to copy anybody.”

Ever the peacemaker, Clifton didn’t take sides; giving in and booking Flatt and Scruggs for later in his season. On the day, the Stanley Brothers performed a couple of sets, and it was also the first time Monroe called former members of his group, The Blue Grass Boys, up to the stage to play with him. It felt like a rose-tinted, nostalgic re-creation of his earlier gigs, even if he alienated his peers in other groups, including Reno, who happened to be observing in the audience.

Reno notably wasn’t invited up on stage, but his manager, Carlton Haney, was making notes. Haney could see that this bluegrass day worked, and that fans would go some distance to see their favourites live. So even though Clifton himself failed to capitalise on his 1961 festival success – instead joining Newport folk foundation to help organise the 1963 Newport Folk Festival – Haney gleefully adopted the ideas for his own weekend festivals, including Roanoke in 1965.

But the real bluegrass wars at Luray were lubricated by alcohol and fired by seething resentment. Monroe could happily nurse a grudge for years, with some harking back to incidents earlier in his career. Professional rivalry spilled over into open conflict, and Monroe’s feuding with Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs (who were originally part of his Blue Grass Boys) was also common knowledge.

On stage, Monroe – who’d be joined by Carter Stanley to duet on ‘Sugar Coated Love’ - couldn’t stop himself from taking a swipe at his former sidemen who had refused to share this stage with him. “It's a shame,” he said to the big crowd, “a lot of bluegrass people you know don't want to be on a show with you or something, if the folks will think you started them. Well, it's the truth, so they shouldn't mind that, and they should be glad they got a start, they’d-a probably had to plough a lot of furrows if they hadn't-a been in bluegrass music.”

Even though Monroe showed his irritation at his famous protégés, he crucially hadn’t named them. But that only seemed to loosen the lips of the now tipsy Carter, who said: “I understand there was a group that some of the folks asked to come in here today. They said no, they didn't want to play… because Bill Monroe and the Stanley Brothers was gonna be here. And that was Flatt and Scruggs. You know, we missed 'em a heck of a lot, ain't we?”

Once the crowd laughed and names were named, Monroe wouldn’t let it lie: “Well, you're talking about Lester and Earl… I started the two boys on the Grand Ole Opry, and they shouldn't be ashamed to come on the show and work with us.” Laughter continued as he added, “I am sure I wouldn't hurt either one of them.” (Listen to the conversation below)

Unfortunately, someone was taping the concert – complete with Monroe’s blatant chiding of Flatt and Scruggs – and a recording was sent to Scruggs and his wife, Louise, who was also their manager. At the festival itself, the crowd’s reaction was knowing laughter, but in the cold light of day Louise Scruggs was furious, and apparently threatened legal action over Monroe’s comments. In short, while Monroe could have lost his place on the Opry and faced a lawsuit at the exact time he was trying to rekindle his career, for everyone else concerned – and for bluegrass festivals – it was a kiss of life and the start of bigger things.

Apart from the immediate boost to the bluegrass festival circuit, the years that followed also saw the genre go mainstream, with Flatt and Scruggs recording a live album at the prestigious Carnegie Hall. The hugely popular TV series the Beverly Hillbillies (1962) used their song, ‘The Ballad of Jed Clampett’, and the movie Bonnie and Clyde (1967) starring glamorous couple Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway, utilised yet another Flatt and Scruggs’ classic, ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown’. Both used bluegrass for hillbilly connotations, paving the way for Eric Weissberg and Steve Mandell’s later smash hit ‘Duelling Banjos’ from the film Deliverance.

Meanwhile, Bill Monroe stuck to his guns with his pure, acoustic bluegrass sound. Yet as the decade moved on, the likes of Jim and Jesse ‘went country’, and temptation reared its ugly head further, with some bluegrass acts even daring to go electric!

There was a glimmer of hope that bluegrass would thrive when cool new bands like the Flying Burrito Brothers enlisted bluegrass musicians Chris Hillman on mandolin and Bernie Leadon on guitar. The inextricably linked Byrds also recruited players who’d cut their teeth in the genre, like John Hartford and Clarence White.

But ultimately, though bluegrass soared with the advent of festivals like that of 1961 and reaped TV and movie acclaim, to keep afloat with the ever-expanding scenes in the 60s, it was a genre that was forced to constantly reinvent itself.

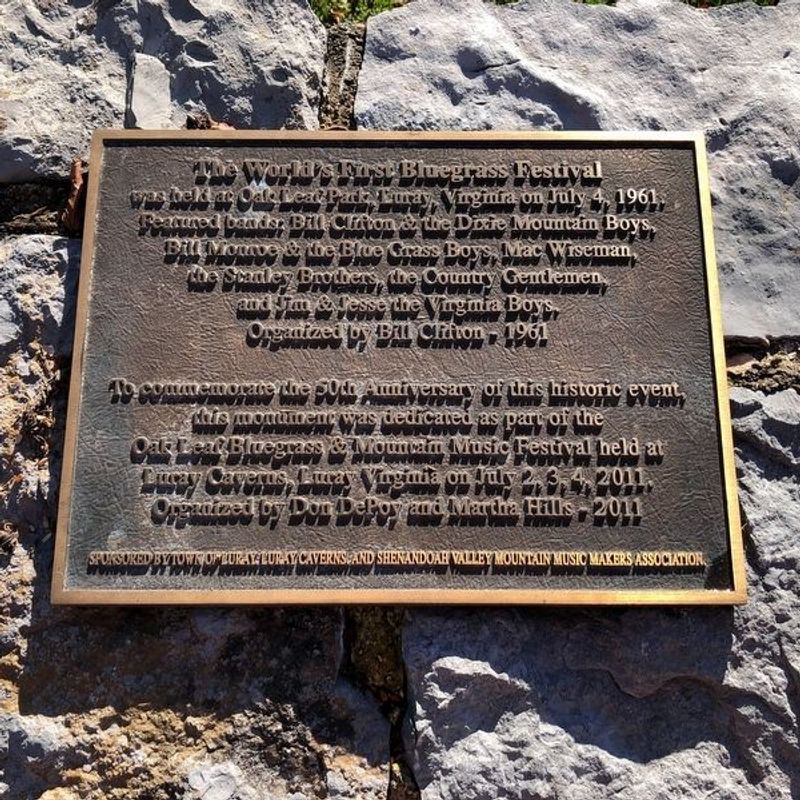

Bluegrass Virginia Plaque