University of Texas Press | 2022

Link copied

Midway through the first verse of ‘Hungry Eyes’, one of several masterpieces Merle Haggard penned in the late 1960s, something surprising happens. Folky guitar picking gives way to a sweeping string arrangement, as Haggard's tale of dire poverty takes on a lavish, dreamy feel. For David Cantwell, author of The Running Kind: Listening to Merle Haggard, those strings contain multitudes.

Cantwell describes them as “luxurious and evoking every fine thing his parents deserved, every meager thing they needed and couldn't afford. Now, here, Haggard has those strings glitter and shimmer all around him, just for show and just because he can. And because they sound like tears".

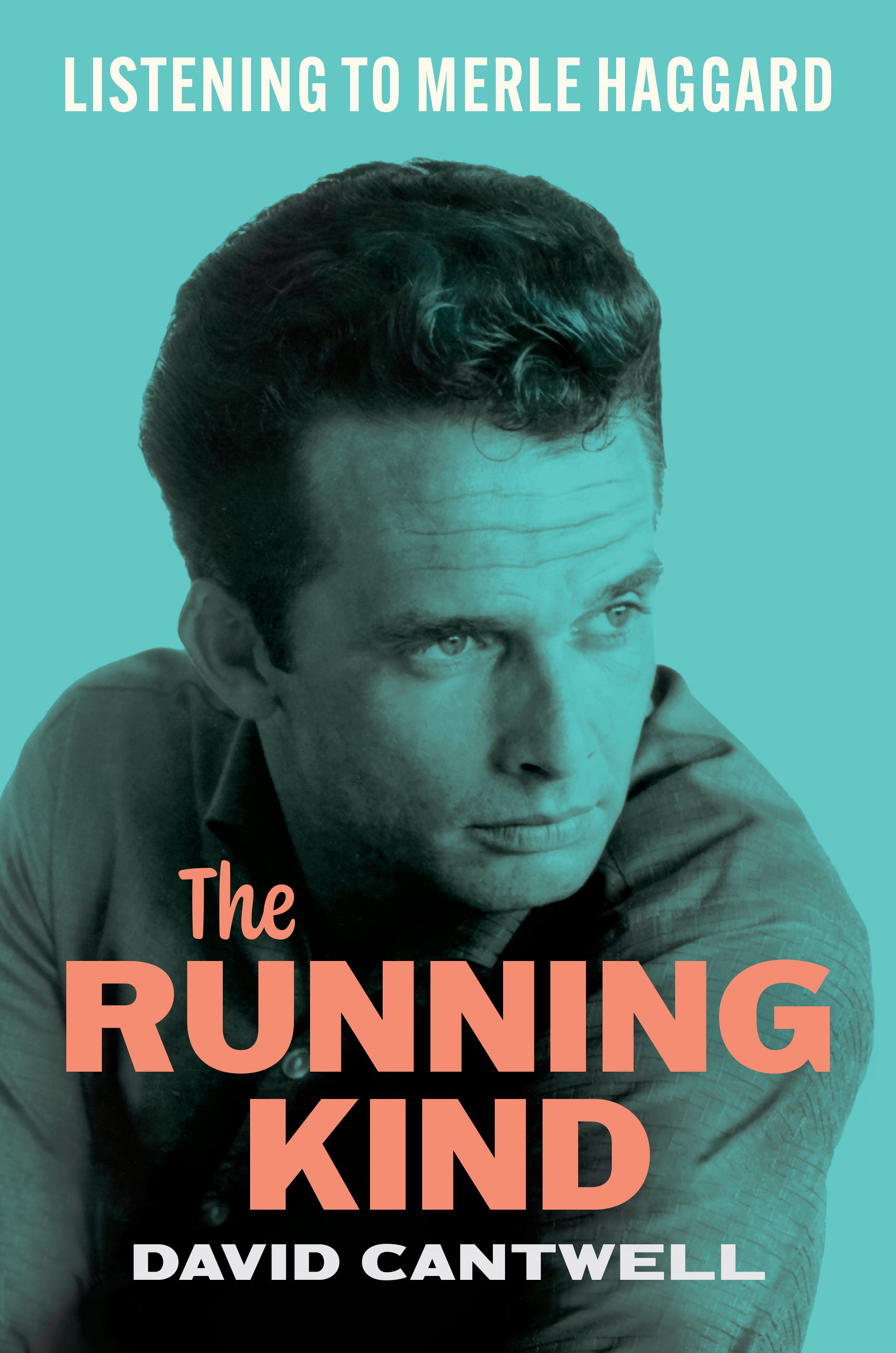

The Running Kind is a revised and expanded edition of Cantwell’s 2013 study on Haggard, first published as part of the American Music Series at the University of Texas Press. In essays on the songs, eras and influences that shaped Haggard’s life and legacy, Cantwell makes a case for Haggard's genius not by leaving out the contradictions that are evident in his work, but by shining a light on them.

In addition to his sensitive close reading of ‘Hungry Eyes’, consider the chapter on Haggard’s ever-controversial hit ‘Okie from Muskogee’. Rather than trying to answer the question of what the song actually means — something which Haggard himself waffled on about for decades — Cantwell embraces its lack of clarity:

"Was that damn song meant to be sung with your tongue in your cheek or with your hand over your heart? Yes."

The Running Kind’s first edition focused heavily on the late 60s and early 70s, when Haggard was at his commercial and creative peak. In the new edition, Cantwell looks more closely at previously overlooked parts of Haggard’s catalog, including the last few albums he released during his lifetime. The expansion also places Haggard more clearly in the context of country music’s evolving sound, exploring his relationship to sub-genres including country soul, Urban Cowboy and even bro-country.

Holler spoke to the author about Haggard’s complicated political legacy, the role of Black musicians in shaping his sound and why we should all reconsider how we’ve been using the word “traditional.”

You use the term “Muskogee Moment” to refer to a defining period in Merle’s career and in America’s political history. Can you explain what was happening at that time?

The Muskogee Moment begins even before there's a song called ‘Okie from Muskogee’. It's this moment in the late 60s when country music is crossing over [into the mainstream]. Almost every major country star of that era had at least one big crossover hit: Sammi Smith with ‘Help Me Make It Through the Night’, Tammy Wynette with ‘Stand By Your Man’, Conway Twitty with 'Hello Darlin'', and on and on. This was also when a lot of pop, rock and soul artists were recording country songs.

When Merle released ‘Okie from Muskogee’ in 1969, it became a lightning rod; in ways that are very familiar with the divisive nature of our culture now. In that moment, he was not just crossing over musically, but his themes were intersecting with the headlines. He wrote the song as a joke, but so much of the nation took it as a protest against anti-war protesters — and civil rights protestors, even though that isn’t mentioned in the song — that he became a symbol of the counter-to-the-counterculture. He became entangled in that very politicized moment in American history, not just as someone who sang about those things but as someone who was identified as one of them.

After ‘Okie from Muskogee’, he wrote a song called ‘Irma Jackson’, which is about an interracial love affair. It's a tender, beautiful ballad that could have crossed over and been a huge hit. But Capitol Records and his producer, Ken Nelson, talked him out of it. They convinced him it would ruin his career. So, instead of ‘Irma Jackson’, he released ‘Fightin’ Side of Me’, and that made it really difficult for people to see any of the irony and humor in ‘Okie’.

You make the case that his politics have been misunderstood, largely because of ‘Okie from Muskogee’ and ‘Fightin’ Side of Me’. What are people missing when they see him as just a reactionary?

Well, I would not want to argue that he never had his reactionary moments. ‘Fightin’ Side of Me’ was certainly a reactionary moment. But it’s complicated. When the Chicks criticized President George W. Bush in 2003 and got kicked off of radio, Merle came to their defense.

He made it plain that he disagreed with their criticism, but he defended their right to speak out and actually embraced the group. He thought they were the most exciting thing happening in mainstream country at that moment. He then proceeded to criticize Bush over and over and over again throughout the 2000s, on albums like Chicago Wind and Haggard Like Never Before.

In 2008, he wrote a campaign song for Hillary Clinton and, if you read interviews from the time, he seemed to really get his feelings hurt when they didn’t use it. Then when Obama won that election, he wrote a celebratory poem all about hope and how exciting that historical moment was. He thought it was amazing that a Black man was elected president.

Merle died in 2016, but he lived long enough to see the beginning of primary season, and he specifically said in one interview that he did not trust Donald Trump. He said, “I think he's dealing from a strange deck.” Lots of white people hated Trump until they voted for him, so I don’t want to make any claims about where he would have landed there, but that was another moment where he went against the stereotype.

He began, at the end of his life, to seem more and more like a mainstream Democrat. Pro-labor, against outsourcing, but always pro-military. He’s not a lefty or progressive, he’s not against the military or even capitalism, but he is for the working stiff. He also, in his own individualistic way, became a big environmentalist. He hated what they were doing to the parts of Northern California where he lived.

Like many country artists, Merle has a complicated legacy around issues of race. What was his relationship to Black music?

On the one hand, he's indebted to Black music to his core. One of his songs is called ‘White Man Singing the Blues’, which names the game of what country music is about in a way that very few country artists have ever been willing to do. It’s odd, though, because I don’t know that I am aware of a direct relationship to a particular Black mentor. His style was replete with Black influences, but a lot of them are influences that he received through artists like Lefty Frizzell, Jimmie Rodgers and Bob Wills.

A thing that happens a lot with white artists, particularly country artists, is they experience these things through other white artists. I'm often unclear how much they're aware that the white artists that they're influenced by were themselves deeply influenced by Black music. When Merle was listening to Bing Crosby’s music as a kid, did he realize that Bing Crosby doesn’t exist without Black music?

A lot of the time, Merle and race get reduced to just ‘Irma Jackson’. But he went to the well of race in America a lot. Not nearly enough, not consistently and with no sense of urgency — typical of white country artists, then and now — but he did do it. He did it 1000 percent more than almost every other country artist of that time.

You write in the book that Merle always held onto his status as a “guarded outsider”, even as he saw incredible success. How do you think he did that?

One way he did that was by staying in California. He was never part of the Nashville scene, even though he eventually moved there for a couple of years just before he married Leona Williams, his third wife. Another way he remained an outsider was by specifically identifying his job as being working class. Merle really identified with the people he was performing for. If you think about ‘A Working Man Can’t Get Nowhere Today’ — a fantastic late 70s Capitol album and hit single — Merle is on the cover dressed in blue jeans, a hardhat and carrying a lunch pail. He’s at the bus stop waiting - in his case for a tour bus - but he sees himself as connected to his working-class audience in that way.

Throughout the song, he sings, “Today, I work my fanny off.” But then in the last verse, he sings, “Tonight, I work my fanny off.” To him, it’s the same thing. Whether you’re going to dig ditches, or work in a factory, or if you have to play a show for three hours, it’s all work. It’s one of my favorite Merle quotes because it really gets to his mindset about what he wanted to be - his artistry always had to be his labor.

The book makes the case that the word “traditional” is often misused in conversations about country music. What are we missing when we throw that word around?

The distinction I like to make is between “traditional” and “retro”. In Merle’s catalog, the most obvious examples are the two tribute albums that he made right around 1970. The first is Same Train, a Different Time: A Tribute to Jimmie Rodgers and the second is A Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddle Player in the World (or, My Salute to Bob Wills).

On the first album, he’s playing a bunch of depression-era songs by Jimmie Rodgers, but he’s playing them like it’s 1970. That record sounds exactly like the records before and after it in his catalog. It’s the modern Strangers sound: An acoustic-meets-electric blend that creates country-soul rhythm tracks, but with lots of folky picking. The Bob Wills record, on the other hand, is retro. He’s actually trying to make it sound like it’s 1945, and he does a great job of it.

Traditional is, by definition, forward-looking. It's about, “How can we take this old thing and make it usable?” Whereas retro is more like, “Wasn't that old thing that isn't around anymore fun?” That isn't a bad thing, but if you're not talking about traditional as being forward-looking — if you're talking about it as being just nostalgic or old-sounding — that's not how it's actually worked. I'm aware that the way I'm using that term is an outlier. That's not how most people talk, right? But I am on a constant mission to get people to tweak what they mean by that expression.

You also make the case that the differences between the Nashville sound and Bakersfield sound have been exaggerated. What do you see as the real relationship between those two styles?

There definitely is a difference between the two sounds, but so many of what we think of as Bakersfield sound artists made Nashville sound records. Merle’s first hit, ‘Sing a Sad Song’ — which was written by the great Bakersfield sound artist Wynn Stewart — is pure Nashville sound; it’s all backing vocals, strings and slick, clean vocal lines. We think of Merle being Bakersfield, but he quickly moved away from those train-track rhythms that Buck Owens did and began to experiment.

Bakersfield was very varied in its sonics. A great example of this is ‘Hungry Eyes’. People will listen to that song and say, “Wow, that could be a Woody Guthrie song.” Except it has this beautiful, Nashville-sounding string arrangement. I give Merle and his producer, Ken Nelson, the benefit of the doubt on that. It wasn’t a mistake, and they didn’t just put the strings there for commercial purposes. They put them on there to help create a particular emotional effect.

The standard dichotomy is that the Nashville sound is supposed to be inauthentic and filled with artifice — it’s pop, it’s not really country — whereas the Bakersfield Sound is supposed to be real, “authentic” country. But I don’t think Merle bought into those things at all. He was all about using the players he had to create a sound that suited the song, and a lot of times that sure sounded like the Nashville sound stuff.

The revised edition of David Cantwell's book, The Running Kind: Listening To Merle Haggard is out now via University of Texas Press.

You can purchase the book from one of Holler's selected partners below:

University of Texas Press | 2022

Items featured on Holler are first selected by our editorial team and then made available to buy. When you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.,

Subscribe and listen to Holler's Best Merle Haggard Songs Playlist below: