Link copied

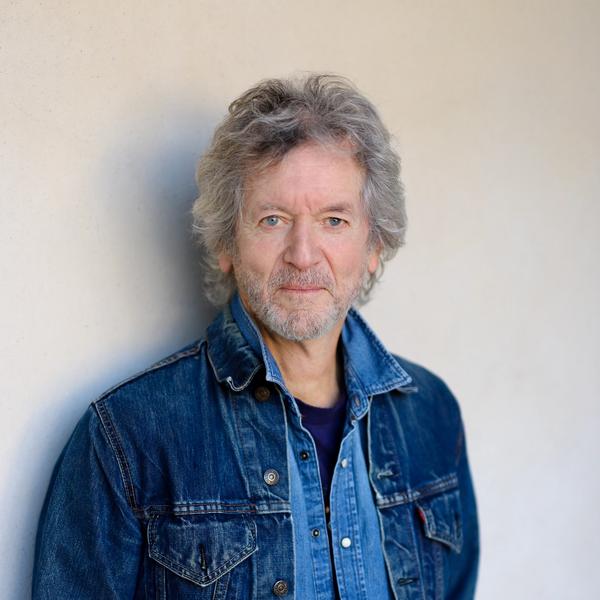

Rodney Crowell is a bona fide living legend. The 70-year-old Texan has won every award going, including most recently the Best Americana Album Grammy for Old Yellow Moon, his collaboration with long-time close friend Emmylou Harris. He was even Johnny Cash’s son-in-law for 13 years when married to fellow country music star Rosanne Cash. It’s safe to say Rodney has seen and done a few things in his time.

As a child, Crowell grew up with music all around him, as one grandfather played bluegrass banjo, one led the church choir and one grandmother played the guitar, all while his dad sang at bars and honky-tonks. When he moved to Nashville five decades ago, Crowell made his own mark as a performer but also as a songwriter, discovered by Jerry Reed and taken under the wing of Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt.

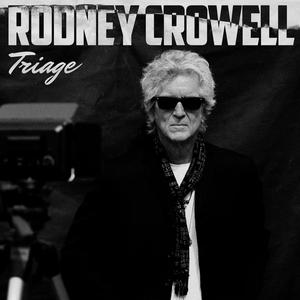

He’s had a handful of career turning points – including joining Emmylou’s Hot Band and having songwriting hits with cuts by Bob Seger, Crystal Gayle and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. Now dozens of albums, multiple collaborations and tours down the line, he’s releasing an incredibly heartfelt album, Triage, which tackles the chaos of the last couple of years in politics, pandemic and climate change, all from his own point of view. Speaking from his cosy home just south of Nashville, surrounded by paintings, photos, awards and memories, he delves into his life and career, all while his dog snoozes at his feet.

What did you expect when you moved to Nashville – and how did the reality differ?

I had no expectations. I was brought to Nashville in 1972 under false pretences. I had recorded an album in Louisiana, and the producer came here to try to get a deal for the music. He phoned me and I arrived with the expectation that I had a 10-year recording contract with Columbia Records and was going on the road for a year with Kenny Rogers and the First Edition to open their shows. Ha! I arrived in Nashville late one night and reality set in; I had to live in my automobile for four months. You can’t make this kind of stuff up. That’s how I got to Nashville; I had no expectations that I was going to be a big star.

How has it changed – for the worse or the better?

It’s changed as the whole world has changed - why wouldn’t Nashville and the music business do the same! For the better though? I’m sure in some ways it has. For me it’s changed for the better; I enjoy what I’m doing now more than ever. But what I do now has little to do with anything about Nashville. I live here for two reasons; first, all of my children and grandchildren live close by - I’m a patriarch and I’m not going leave them. Number two, the collaborative possibilities in Nashville are unending; musicians here are wonderfully creative and I have access to that talent. I don’t give two shits about the industry, it has nothing to do with me. Back in the ’80s, I was all up in that, but not anymore. I’m an independent artist and Nashville doesn’t mean anything to me.

Did you always think you’d end up in music – like your musical grandparents and father?

I never felt that way, but in hindsight, yes, I was destined to do this. I haven’t done anything else since I was 22 years old. I was a dishwasher for a little while and that gave way to getting a job as a songwriter, which in 1972 would mean I got paid 100 quid a week, which I could live on. I lived modestly and I loved it, but that doesn’t exist anymore.

When I came to Nashville, I became friends with Guy Clark and songwriters like Townes Van Zandt, Mickey Newbury and David Loggins, and it was a time when the industry itself was hands-off on songwriters. They had no monetary investment in us, so everything we were doing creatively was amongst ourselves. We would gather late at night and imbibe drink (and other things) and play songs for each other and give each other input – we’d be brutal sometimes. It was a great way to learn how to write.

In the industry now, as far as I understand it, if somebody in their early 20s comes in, they immediately start hooking them up with other people, saying: “if you write a song, we can get it recorded by so-and-so on Tuesday”. When I came in, they just left it to us to talk among ourselves and figure out how to write good songs. Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Paul Simon and Neil Young were already out there. Johnny Cash and Kris Kristofferson were writing really good narrative songs. There was no market to write for; they were writing for what the songs were, not who could record them on Tuesday and make X amount of money!

It feels like the big turning point in your career was when you joined Emmylou Harris’ Hot Band in 1975.

When I first came to Nashville, I joined that group of songwriters with Townes and Guy and it really was a focused songwriting salon. Then at Emmy’s invitation, I went to California and joined the Hot Band, where I was surrounded by top-drawer musicians. It was a great education for me because I went from the craft of lyrical songwriting to being with musicians, where the next thing to learn was how to arrange music and understand the language of doing so. There was James Burton and Glenn Harding – and Emory Gordy from Elvis Presley’s band – coming to play with us.

They spoke a musical language I did not know, but I’m a quick pretty student, so being around those musicians, I learned at warp speed how to communicate chord changes, time signatures and that kind of thing - it was so valuable to me. Add to that the fact that I was suddenly on a plane going all over the world - London, Brussels, all these places I’d never been. It broadened my scope of what the world is really about, it’s like the blinders were just peeled off. So you’re right, joining the Hot Band was the paradigm shift in my development as a singer-songwriter, producer and all-around performer. The things that I learned then I’m still using today.

Do you still bump into Emmylou – and see Vince Gill and Tony Brown from your ’70s group, Cherry Bombs?

Of course! Vince Gill and Emmylou are two of my closest friends. Yesterday I was walking my dog when Emmy was walking hers – we were talking on the telephone at the same time! We were in Texas together a few days ago; we travel together. Vince is like a blood brother to me – I see him regularly and I talk to him all the time – and it’s the same with Tony Brown.

It must have been amazing hooking up with people like Guy Clark and Townes van Zandt?

They were older; they had seven and nine years on me, which was a millennium in experience, and I could just tag along like a nuisance and learn. I don’t know that that exists anymore.

If you make good music, money is going to come. But to chase it, to bend your creativity toward what is going to make money for you, is to put the cart before the horse.

Do you feel at home in Americana?

Well, I certainly understand what Americana strives for, which at its best is music made for the sake of the music – not for the sake of the almighty dollar. Of course, if you make good music, money is going to come – and it does. But to chase it, to bend your creativity toward what is going to make money for you, is putting the cart before the horse as far as I’m concerned.

Americana at its best is the kind of music you’re not going to hear on commercial radio stations because it requires you to stop and think. Commercial radio stations only want you to think about the commercials, the products they’re selling. Music is secondary to advertising on the radio, so it’s no wonder that the kind of music that’s programmed in that format is music that is designed not to make you think. They don’t want you to stop and think about a lyric that I’ve written and miss the commercial for hot dogs!

How was making this self-released pandemic album, Triage, different from your other projects? Did you self-release it to have more control?

When I think about it, it was certainly about control; I don’t have to answer to anybody but me and my co-producer, and my wife and my dog. Come to think of it, I’m not that free! On the record, I knew I was going to take a serious stab at articulating my take on monotheism, and from that I quickly went into climate change and economic inequality, all of it. Is there one God? Is what we’re doing to the planet an existential threat? Is there anything we can do about social injustice? I knew that those were themes I felt strongly about and wanted to write about. One thing the pandemic offered me was a minute to take a deep breath and look at what I’ve done – and I’m not trying to preach or convert anybody to my vision of anything - but I was trying to share it in the most neutral, well-grounded language I could find.

I like the vibe you’ve got, it reminds me of the Robbie Robertson record with Daniel Lanois, especially on the half-spoken ‘Transient Global Amnesia Blues’

I know the album well of which you speak, the song is called ‘Somewhere Down the Crazy River’. There’s also a Robbie Robertson album called Contact with The Underworld Of Red Boy that was very influential to me. I meditated on that and listened to it for a long time – same with the latter output of Leonard Cohen, starting with ‘Waiting for The Miracle’. You’re right though, you’ve got your finger on something that’s there for me.

My musical exploration in the time I’ve lived on the planet has shown me certain things need to be expressed organically, and the drama of the half-sung spoken word always appealed to me. A lot of that comes from when Guy Clark and I spent time talking about writing songs back in the ’70s. We used to look each other in the eye and speak our lyrics. That came from Guy listening to Dylan Thomas and his poetry, like Under Milk Wood. We need to be able to speak the words to our songs just as well or better than when we sing them.

How did your climate change song ‘One Little Bird’ come about?

That came to me like a lightbulb on the hilltop I live on. The birds had disappeared in late 2019; I stomped around in the forest looking, and just couldn’t find any on my property. One day I was sitting out back with my guitar, thinking about another subject for a song and a little bird sat in the tree looked at me and started singing. So I listened to this Carolina Wren bird, and translated what I thought she was telling me into this song. It’s about trying to make amends with someone, and this one little bird is trying to suggest that we should try to make amends to the planet.

As I’ve gotten older, I understand that we start to fold ourselves back inward, back to our inner landscape, because our mortality is not so far down the road.

‘This Body Isn’t All There Is to Who I Am’ is about mortality - I wonder if you have been more contemplative during the pandemic?

Here’s the thing, as a younger artist there was a period – in my 20s, 30s, even in my 40s, maybe bleeding into my 50s – when my expression was through wanting the world to give me recognition, money, fame, a girlfriend who became my beloved, all of the outward things you want to claim as your own. As I’ve gotten older, I understand that we start to fold ourselves back inward, back to our inner landscape, because our mortality is not so far down the road. I believe we instinctively start to try to understand ourselves spiritually because we know there’s a transition coming…

So, looking back on your life and career, is there anything you wish you’d done differently?

Had I known then what I know now, I would’ve done a lot of things differently. But I doubt that I’d have made fewer mistakes - I still would’ve found plenty of mistakes to make!

Rodney Crowell's new album, Triage, is out Friday July 23rd via RC1 / Thirty Tigers - watch the video for single 'Something Has To Change' below.

Photography by Sam Esty Rayner / Claudia Church