Link copied

Lori McKenna is ensconced in her music room, perched in front of a dozen guitars, a piano and two cosy chairs in her home near Boston, Massachusetts.

Self-deprecating even as she hoovers up awards and chart-toppers, she’s been the go-to songsmith for everyone from Taylor Swift and Chris Stapleton to Little Big Town and Maren Morris – sometimes writing solo and sometimes as one third of the Love Junkies, with pals Liz Rose and Hillary Lindsey.

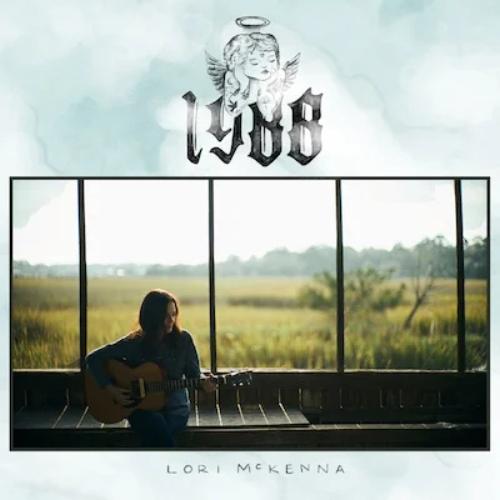

But right now the singer-songwriter and hit-maker is packing up to go on tour with her own album, 1988. We caught up with her to discuss writing with family, the role of AI in songwriting and the stories behind the songs on 1988.

How has this last year been for you?

It’s been great. I’m writing more than ever, all because of Zoom. It started in such a sad place because of Covid, but now we’ve all moved over to writing on Zoom more permanently. I’m not in Nashville, I live just south of Boston, and before this I was writing five or six days a month. Now I’m writing three or four days a week – though not right now, because I’m starting the album cycle and touring. But I’m such a homebody and I love writing, then just walking upstairs into the kitchen and making dinner.

When you’re writing on Zoom, do you literally have a split screen and talk back and forth?

Yeah, you can’t sing together, obviously. You end up in trouble sometimes because you can’t always hear where the beat is. In that case, we record on our phones and text each other what we’re hearing. The guitar part can be a little hairy, but for the most part it works, especially if you know the person well or feel comfortable. Then we recorded this album over a couple of weeks around Halloween last year in Savannah, Georgia.

Is that in Dave Cobb’s studio?

Yes, it’s a brand new studio. The last two records I made with Dave were at RCA Nashville, and the first was in his house in Nashville. He’s still running things at RCA, but found this house on one of the tiny islands off the coast of Savannah where he grew up. It’s crazy - you walk outside the studio and there’s a pier and we saw deer running across the water and dolphins swimming. I mean, where do you have deer and dolphins?

Does this record move you more towards Americana and rock, rather than folk and country?

Well, I called Dave and told him I wanted to make a rock record. Everyone’s still teasing me because it’s not really a rock record. Every song I write, I hear ballads. 20 years ago, people said, “You’ll start to hear all the parts as you’re writing - you’ll hear piano, strings or a bassline”. Never! I hear nothing! I hear voice and guitar and… nothing. No production skills are in my head at all.

So I said to Dave: if I made a 90s rock record, what would it sound like? Then I realised I actually made records in the 90s. I guess I forgot how old I was! But you know, the Gin Blossoms and Sheryl Crow records from those days still sound so good – and this was as far as he’d let me go with that. We tracked everything live, then Dave brought all my 90s rock dreams to life.

It sounds like you’re back in the groove of being a workaholic when writing?

I just love writing, it’s my favourite part. And it’s funny – I’ve had this conversation with other writers a lot – I tend to get burned out more than I did years ago. I’ve learned that I just need empty space.

My youngest son just graduated high school – he’s homeschooled the last two years, and my daughter is home doing college online. Some months I’m not alone in the house, so I have to carve out space for myself. I’m pretty good about not letting myself be a workaholic; I try to keep a balance. I don’t want to overwork, and make sure I have a couple days’ space when I travel. I always say if I’m gone three days, I need two days to recover. Now I’m older, if I’m gone three days, I need four days!

So you don’t have to go to Nashville all the time to co-write now?

Yeah, although I still go about two or three times a month. Two of my kids live there, and they’re both songwriters – and we bought a little condo down there before Covid, so there’s a home element. Before I’d mostly stay with Liz Rose at her house, but we’ve something there ourselves now. So I wash dishes and flip pillows, and there’s something I like about that.

For so long, McKenna has been the creator of timeless, homespun tunes for other artists and bands. Now, with

Is there a tension between the creativity that emerges from Nashville and the reactionary people running Tennessee?

I don’t know. Of course, I’m up here living in Massachusetts in a very different world. When I’m down there and those discussions come up, they still seem unbelievable. Sometimes I’m like, “No, that’s not right?”, and my friends say, “Oh, it’s true”. I don’t know where it comes from and I won’t pretend to be able to answer it.

These conversations come up in other ways. Like, how are songwriters going to make a living with no-one buying records anymore, and streaming and all those things? We sit down with coffees and talk or cry or grab each other’s shoulders and say: how are we going to write the best songs? How do we find a different way to say we have to love each other more than anything? Because that’s the job.

I must ask what you think of the idea of AI writing songs?

Oh, gosh, this is such a new topic to me. I was on a committee meeting where a songwriter I really respect explained their point of view on this, about how it can be helpful. I was at first shocked, then I called another writer who said it might end up being like sampling back in the day, when people started sampling pieces of songs. In the beginning it was: this can’t keep happening – and now it happens constantly. I’m not in that world, because I still write with a guitar in my hand. But I don’t think it’s going to go away. It’d be great if we figured it out real quick, but I don’t think we’re going to.

Your songwriting go-to words and phrases used to be kitchen and front porch, and I wonder if you’ve any new additions to the McKenna thesaurus?

Ha, it’s terrible! They’re still the same. I do that with backyard stars too, meaning a sad sense of time, back when you were a kid in your own backyard. I keep doing that, ever since ‘Humble and Kind’ [written for Tim McGraw] brought that out. Back in the day, I was writing a lot about being married to someone you can’t find or who drinks too much. So there were the drinking years, the freedom years, the escapism years, the balance years… and now I’m stuck on age!

You’ve said you shy away from politics, but surely writing about ageing and how older people are treated is political? Plus you’ve songs about addiction like ‘Wonder Drug’, which is pretty political.

It’s funny, I don’t think of them as that. ‘Wonder Drug’ is a story that’s very prevalent, and you’re right, there’s a political part of that. I understand the emotional side of political things, but not the logistical side. We’ve watched so much change in the world and my first instinct is to shy away and stay in the room I know, which is usually the kitchen.

Even with Thanksgiving, when the family gets together and somebody wants to talk about something someone else doesn’t agree with… those things are still hard for me. The only way I can understand is through a friend’s experience – it all comes emotionally first. So you’re right. The technical side of ‘Wonder Drug’ – and why are people being prescribed it – is a road I don’t know how to go down, but unfortunately I do know how to watch somebody lose somebody that way and how difficult that is.

You describe yourself as a selfish songwriter, holding onto songs for yourself. But do you ever have others in mind for songs like ‘Killing Me’?

Yeah, I pretty much send everything to my publisher and wait for their notes. They can tell ‘1988’ is a song about my experience, being married and building a family, and it’s not necessarily going to apply to somebody else. We wrote ‘Killing Me’ specifically for this record, with Hillary Lindsey and Luke Laird, because I knew they could help with that 90s rock sound. If somebody told me that Miranda Lambert really wanted this song, I would’ve said ok! I’m so lucky to be part of that community that if Little Big Town wanted to cut it, they’d probably be okay with me cutting it as well.

How did you collaborate with Tim McGraw on his new album?

A lot of times when I’m writing, Tim is right there in my brain, especially if I’m co-writing. He’s such a song person, and digs into songs. The reason I have a job is because of Tim McGraw and Faith Hill, they’ve been so great for me.

For the songs we’ve written together, Tim and I always collaborate like this, where I’ll get a text “Happy Mother’s Day. What do you think of this?” So you can tell the wheels are turning! He sends ideas, but still listens to songs I write alone or co-write. Yet we’re never in the same room. It’s always in passing, and then we work on it to add meaning until it’s right.

How does it feel when you write with your sons – Chris on ‘Happy Children’ and Brian on ‘1988’, which is about you and your husband, Gene? How do your roles divide up?

It’s like any other co-write where you know them and their strengths, and everyone finds a spot in the song, which is one of my favourite things about co-writing. Brian is really melodic and a great guitar player. Plus he’s the reason my husband and I got married when we were 19. We all came together in the beginning of this family unit of ours – established in 1988. The idea came from a tattoo my daughter got, and I wanted to write it with Brian because he’s been my sidekick. Our kids are our greatest teachers, and my kids are no exception. I was also blessed to be able to write ‘Happy Children’ with Chris. That song reminds me of the 90s singer-songwriter vibe, and Dave Cobb was a big part of bringing it to life in the studio.

Tell me about the emotional song ‘Days Are Honey’ you wrote with Barry Dean and Luke Laird?

It came from an old expression: some days are onions, some days are honey. It’s so true, and usually it’s a bit of both. I love the idea that as long as you still love me, we can get through the dirt part. You can write anything with Barry if you pour your heart into it; you find a way to make it happen.

One that really moved me is ‘The Tunnel’. What sparked that off?

I wrote that with Ben West and Stephen Wilson Jr, who are amazing. It came from growing up with people that live down the street, and looking back at some of those who are still struggling, it’s one struggle after another. Why has my journey been different? Why did I get to be lucky? It popped into my head that sometimes life is mostly the tunnel for people.

I remembered that down the street from my house, there was this tunnel underneath the road that took a brook from one side of the road to the other. Kids used to dare each other to go across, and I only got about four steps before I ran out the other way, I never had the guts to do it. Then I thought of all the crazy things you do in middle school when you’re a kid and brought that idea to Ben and Stephen Wilson Jr, who said they’d been trying to say this for a long time. So we figured it out together.

I feel I’m a positive person, but I do like sad songs, and never saw the light. It was Stephen who said: when we get to that point in the song, just say there’s a light at the end, keep running, give them the light. I wouldn’t have done that by myself, to be honest. It was a good day writing with those guys.

Finally, what’s the best thing about getting older?

Oh, God, there’s a lot. I should write a list. I’m hesitant to go down any political roads, but I’m starting to know how to at least have my say, via emotions and the human side. Plus I know I need space and need to be creative – and need to sit and be quiet too. I love having adult children, having dinner with them and talking about the way they’re experiencing life, because that helps me understand how I’m experiencing it. Oh, and I think I tell the truth more.

---