Link copied

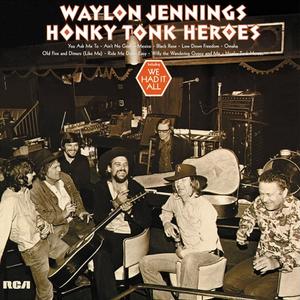

Back in the early 1970s, the original outlaw country movement started in reaction to Nashville's lean, formulaic writing and slick production. Artists such as Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, Jessi Colter and Tanya Tucker considered such gloss sacrilegious. Looking back from now, they likely had no idea how average and linear country music could - and would - get. Thankfully, the outlaw country counterculture carries on, with contemporary flag-wavers like Margo Price, Jamey Johnson, Shooter Jennings, and a certain Elizabeth Cook.

Cook's latest release, Aftermath, further solidifies her standing, not just among country outlaws, but as a bona fide rocker, as well. Produced by Butch Walker, the record finds Cook continuing to sift through the ashes of her life, rising from them as the artistically indestructible phoenix that she is. In song after song, she is at once fragile and defiant. Free of any external - or internal - constraints, Cook bares her soul, crafting these stories with equal measure of self-awareness and self-deprecation, resulting in a thoroughly potent piece of work that breaks all boundaries. If that ain't outlaw, then nothing is.

Elizabeth Cook

Lest anyone think you're just a rock star, which you are, but in addition to making records and touring, you also have your radio show on Sirius XM, your new fishing show on Circle TV, your Squidbillies role and more than 400 appearances at the Opry. I know it's hard to say no when dreams are coming true, but how do you balance all of those different things?

I don't. It's a constant state of damage control [Laughs]. I have to stay pretty active or I go to places that aren’t so good, so it's kind of a survival mechanism on some levels. I've never been a person that knows how to be bored or slow down, it's not my nature. I always find a thousand things to do. When I do need to slow down, I have to make a real focused effort to do it, it doesn't come naturally.

There's a whole riff in your bio about how you spent your 20s being part of the Nashville machine, writing what you thought people wanted to hear. You've never struck me as someone willing to kowtow to anyone's bullshit or cater to any lowest common denominator. Tell me about getting caught up in that system and then getting out of it?

I think it's pretty common, especially for females in their 20s, to be raised in this society to behave with a certain amount of reverence to a social system. Certainly what I was exposed to was a pretty rigid path, and I didn't know that there were any routes that I could go with music that didn't include striving to be Reba McEntire. That was my only reference coming out of rural Florida and Georgia, so that's what I set out to do. It was on the heels of that neo-traditional movement that happened in the late '80s and '90s.

But by the time I got to Nashville, got a publishing deal and made a little indie record, it all shifted. Country music artists were starting to become arena acts like Shania Twain and Garth Brooks. They were manufacturing CDs at 25 cents a unit and selling them for $25 a unit. Radio had deregulated and was owned by two massive communications companies, and the payola system was in full swing. I was disgusted by that. I had worked toward getting this holy grail of a major label record deal with quirky, funny as hell country songs, but the music that they wanted was not the belt buckle Reba; it was Faith Hill in a ballgown singing about breathing to an orchestra. So it was such a heartbreaking misfit of trying to put a piece into a puzzle that just wasn't going to fit.

I had so many accomplishments along the way though, getting to play the Grand Ole Opry and having a lot of validation from people around the industry that did like what I was doing. There was this fateful moment where David Macias started Thirty Tigers. I went into his office to explain to him that, even though I was deal-less, I was putting out a new little record and I was going to be fine. So it's been a slow build since then with some disruptions, but that is how the universe navigated me through all of it.

The humanizing of someone's experiences is a great service toward humanity; doing it through music is a beautiful delivery system.

I feel like our lives are so much more nuanced than we publicly portray. Social media and cancel culture make it almost a crime to have complexity and fallibility in our human existences. We build people up and then stomp them down when they don't meet our imagined expectations. To me, songs, when they're real and true, help peel back some of those layers to get to the humanity and hopefully inspire some empathy. What's the point otherwise? Right? Do we need more songs about beer and boobs? I don't think so.

I think there are two facets. There’s the cheap, low-hanging fruit route, I've done some of that. I wrote 'Balls to Be a Woman' and 'Yes to Booty'. I like a good time in a honky-tonk, I'm not opposed to that, but humanizing people helps with our acceptance of them, because you just see more things to relate to - so you're less critical of the things that you want to do and that we're taught to judge. So, yeah, the beer and booty songs can be way overdone and really cheapen the whole medium of music and songwriting.

Country music, especially.

It has dumbed down our culture to a tragic, tragic extent. Also, on the other hand, songs that are just flat-out protest songs that do nothing but preach facts, “This is right and this is wrong”, I don't like that approach. Everybody that agrees with you is going to be like, "Fuck yeah!" and everybody that doesn't is going to tell you to shut up, you know? I think the route of getting people to step inside someone else's shoes, to have more compassion and understanding of complexity and nuances in folks' lives, is best done through a storytelling projection - if it's not about a specific person, but about a character like a “Heroin Addict Sister”, "Stanley by God Terry" or "Mary, the Submissing Years." I like to do it through storytelling and a character framework when I write songs. The humanizing of someone's experiences is a great service toward humanity; doing it through music is a beautiful delivery system. Yeah, I don't like preaching and I don't like stupid.

So the new record, Aftermath, picks up and expands on some of the things that you started exploring on Exodus of Venus back in 2016, after you went through a whole bunch of tough stuff. Even if time hasn't completely healed all of that, has it given you a different, wider perspective?

Totally, you make a new deal and hit the reset button on your strength and your power. You need a relationship with your own strength in a very visceral way, and only in that moment can you even conjure that type of strength because you have to. It's like a survival instinct, and you're never more powerful than you are right there in that moment, so it just renews your whole relationship with the power and the strength that you do have, and that's very liberating. Watching so many people close to me die and helping them in those last moments, I've lost some of my fear of death because I know what it looks like, and I have to accept it. So it's not this unknown fear. It's confronted me in very realistic terms and that's so empowering. When you lose your fear of your mortality and try to keep your good sense and not let that inner self-destructive territory, it's a really, really powerful place to operate from. So there's a lot of creative chances and places you can go.

Everything about the first few songs on this record is just badass. I wonder how much of that comes from the fact that there's this defiant style in the music, but then this vulnerable substance in the lyrics, like you're laying yourself out there. Does having that edge to the sound make it a little bit easier to be vulnerable?

You can use it to build some armor around you. I mean, for 'Bones', I'm literally talking about wearing my parents' ashes, and I didn't want it, it's just what happened. What I was trying to say just had a tribal feel. So that's why, when I first wrote it, I just started humming that tribal part, because it is about my tribe, about bones and ashes, things that we attribute to a deep sense of spirituality with the Earth. So that's what made sense there. “Perfect Girls of Pop” is just sort of getting washed away in this high-tech new world, not knowing who you are yet and not being equipped to express it.

I refuse to force it. I refuse to make myself sit down and, as a lot of folks on Music Row will say, "Let's sit down and write one".

With "Daddy, I got love for you", your line is “Sittin' up in bed with stage 4 cancer / A chew of tobacco and all the answers”. My father had pancreatic cancer, a glass of wild turkey and none of the answers, so not quite the same, but I get it. How much closure do you get from finally putting something like that into a song and putting that song into the world?

A tremendous amount. When a song is nagging like that and you finally get it, it's like killing a fly buzzing around your head for a year. So it’s extremely gratifying when you finally get closure on one that's been floating and formulating forever. But again, I refuse to force it. I refuse to make myself sit down and, as a lot of folks on Music Row will say, "Let's sit down and write one." I don't sit down and write one. That whole thing pisses me off, like "Sit down and write one... What are you talking about?" These are like Bible verses. You don't just sit down at 10 a.m. on a Tuesday and write it.

A lot of people do [Laughs].

They suck, mostly. There's some that are good at it, I guess I'm not one of them.

Elizabeth Cook's latest album, Aftermath, is out now via Agent Love Records / Thirty Tigers. Listen to ' Daddy, I Got Love For You' below.

Photography by Jace Kartye.