Link copied

“Anyways, very revolutionary phone call,” Cam says, cheerfully apologising for another long explanation of what it means to fight for inclusivity in a genre as homogenous and hidebound as Music Row-made, radio-oriented country music.

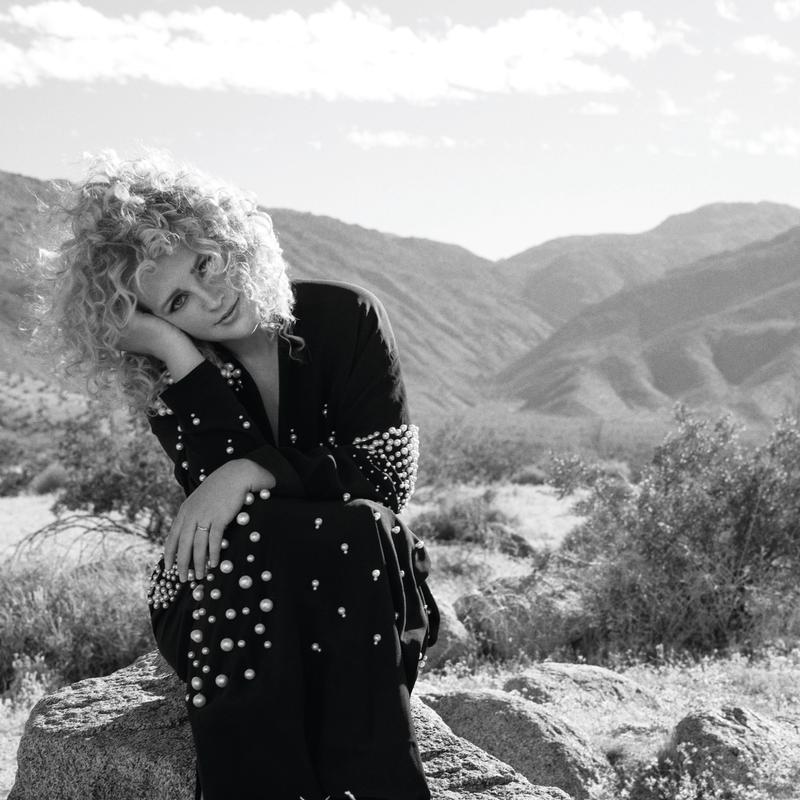

The 36-year-old singer and songwriter just released her long-awaited sophomore album The Otherside — a follow-up that sometimes seemed like it might have fallen victim to Nashville’s relentless sexism, in spite of Cam’s double platinum 2015 single ‘Burning House’. But the music, expansive and ambitious without losing its warm, acoustic country roots, is only part of Cam’s mission. She’s just as passionate about dismantling broken cultural and political systems, a task she approaches with optimism and effervescence — as is clear in this interview, which was frequently punctuated with self-deprecating laughter. The music and the work are of a piece, evidence of a quest for art and community that’s both open and liberated, and all the richer for it.

You had your first child almost a year ago — how has becoming a parent impacted your career as an artist, and has it changed your perspective?

I remember going into it being like, "I'm a failure if I don't get it all done." — so I did a European tour while six months pregnant, filmed the ‘Till There's Nothing Left’ music video when I was eight months pregnant, and honestly was really pushing to have the album come out while I was pregnant. I was so like, "I CAN DO ALL THE THINGS." Not to get really deep, but capitalism — this idea of ownership and "Time is money" - when you have a baby, your time's not just yours. It's not that you're giving it or not giving it, it's just ours, all together. The do-it-all mentality just sets you up for a lot of heartbreak, because the world isn't even gonna allow you to do it all. You need community, you need help, and that's not a weakness, that's a super big strength.

The narrative that's always existed - that country music is conservative only or white only - is a narrative. It's really been made up.

Not many country artists are bringing capitalist critique into album promo. How do you feel politically connected to or disconnected from the country music mainstream?

I've actually been really comforted. The narrative that's always existed - that country music is conservative only or white only - is a narrative. It's really been made up. The more I look back and read up on things, I find that there's plenty of people that have been here and had all kinds of ideas. What used to unite people on the music end was more of a class thing, but on the industry end it definitely was created purposefully. In the '20s and '30s, the industry created musical genres, and would only record and market white musicians - they wouldn't record the Black country or hillbilly musicians. Anyone who was a Black musician was put into the ‘race record’ category. All those labels — they're not real, but we have been handed this legacy, and we've been living in this legacy for a really long time. Like [writer] Andrea Williams, when she talks about how baseball was segregated. Besides the morality of it, are you really playing the best game when you're living under this kind of fake division? It all does come back to white supremacy and capitalism. We have to be really intentional and effortful about how we go against that.

You are on ACM and Recording Academy diversity task forces — what does it mean to you to try and do that work through institutions that obviously really struggle with inclusivity?

I ask myself the same thing, every day. First, being in those spaces, I believe I have access to a lot more information. When they're discussing the problems that are going on, if I'm in the room, I actually get to hear all the problems. Not a lot of people get to be in those rooms, so I should show up.

Second, how things are playing out in these smaller structures and organizations is just how they're playing out in the bigger structure. This setup is not unique, and these ideas are not unique. They have been crafted for 500 years; it’s very purposeful. You're gonna run into the same assumption of meritocracy when you're trying to explain why people should be allowed in a certain category of country music nominations, as when you're talking about systems that are supposed to be in place to help people in the United States. A lot of the same logic and arguments show up.

I think it's important to act within systems that you know are problematic. This year’s ACMs had three Black artists that did not have nominations who were given airtime; backstage, Dick Clark Productions and ACMs made sure that there was much more diversity in the crew that was working and getting artists around. Those might sound like really small wins, but that happened because I was bothering people and started a diversity committee, and there was a group of people that wanted to show up. People from different groups came and educated us, and we talked things through — and yeah, of course, it is not solved. Like not even close. But I saw something shift.

Should we put all our eggs in that basket? No way. When people ask me, "What is the solution?" I'm like, "What are the solutions?" They're from all different angles: you've got to work in it, and you've got to work outside it. There are Black female-lead organizations, and those are the people that I want to help build something outside, something that's new that doesn't come with all the same baggage — you still have to be very intentional, and try not to bring that baggage back into it.

There are a lot of artists working in Nashville that are still afraid to even talk about this stuff, because they're not trying to mess with their money.

If you don't know any better, I mean, I don't know what to tell you. But if you know better and you don't say it, you are closing the door for what might be thousands of people behind you. Even when you show up and think you're doing a good job because you're the white woman saying, "Oh, I'll show up and fight for diversity" — if you don't have enough awareness to see the full picture, and if you don't go so, so hard for Black women, for Black, disabled queer women, for the people who need it the most, we are not all going to get there.

I'm saying this from a position of someone who is signed to a major label, who has great support and money behind me. I'm not coming from the outside, and I have to acknowledge that that means that somewhere along the line, I have compromised, and accommodated, and perpetuated. I just want everybody to know, if you're one of the few people that gets in, that doesn't mean the thing's saved. You're just one of the safe options. You really have to be like, "I'm coming in, but everybody has to come with me."

I have to acknowledge that I have compromised, and accommodated, and perpetuated.

So often, it feels like an uphill battle just to get baseline acknowledgement of how homogenous Music Row is.

Country music has been made, and we continue making it, a safe space for people who hate other people. Those people feel like they can come in and say anything, and it's just like, no. If you're not ready to support and be like, "I am here for LGBTQ people, I'm here for Black people" — maybe that's not your language yet, but you definitely cannot be here saying “anti-” and hate. It hurts when people from outside of country music assume that country music is, like, about that — that racism and anti-LGBTQ sentiment is one of the main parts of what we are. It's not true — that's not how the music's created, that's not how the community exists right now.

Country music has been made, and we continue making it, a safe space for people who hate other people.

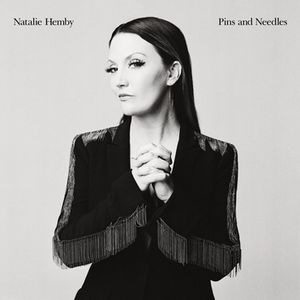

You mentioned just how deep the inequality is even for white women in country music, and ‘Girl Like Me’ is clearly about that. I know your co-writer Natalie Hemby had tried to make it as an artist before becoming a songwriter, and that your path to a sophomore album and country music overall wasn't exactly smooth — what were your guys' conversations like as you put that song together?

Natalie started playing the verses, and I was like, "Oh my God, that is so sad." She goes, "It's your story. It's your comeback story." I wasn't ready for someone to like, tell it to me about me. Then we got to the chorus, and she was like, "What do you think this should be?" And I said [she starts singing], "They're going to give up on you, you're gonna give up on them." I know, it's sad. And people are like, "That's too depressing."

The truth is, there are these story arcs that you struggle through, and then yay, you've made it, and that's the end. But at some point - and this happened to me during these last five years - the world just breaks your heart. It just isn't what you thought it was going to be. Then what? Do you stay jaded and say, “It's not worth my time?” Like what we were talking about earlier — "This system is just so messed up, so why bother?" Or do you say, which is what I said to myself — "No, just 'cause it wasn't what I thought doesn't mean there isn't still space for so much more." Just because the concepts I had were wrong and got broken, it's actually a freeing thing to see the big mess for what it is. There's just streams of glittery gold and then there's puddles of muck, and it's everything, and you need be in it instead of binaries and good, bad, whatever. You get to start swimming in it for real.

The Otherside - the new album by Cam - is out now via RCA.

Photography by Dennis Leupold.