Link copied

Every now and then, out of the bedazzled masses of bro-country peddlers and American Idol castoffs, a savior emerges, someone sent to wash away our Hot Country sins, purify our palettes, and singlehandedly remold the genre into what was originally intended.

They arrive bearing a brilliant fanfare of both twang and something resembling truth, a revolution that cuts through the Music City homogeny. They provide something that is not so much fresh as it is familiar, something that reminds us of what country music used to be: sacred.

The same notion arises every decade or so alongside this musical messiah. It is the idea that country music needs to be saved. But something must first be in danger for it to truly need saving. So what is country music in danger of, exactly? Evolving? In truth, the genre doesn’t need rescuing. It never has.

Since its documented origins in the 1920s, country music has witnessed a vast amount of change, so much so that every handful of years is dubbed a new “generation” within the genre. With the dawn of each generation – with the ushering in of the latest set of fads, styles, sounds, and ideals – this conversation of needing to save country music is often sparked, usually becoming an urgent talking point among pearl-clutching purists and traditionalists, the genre’s self-appointed gatekeepers. And why? Because something, be it an artist or some new noise, comes out of the left field to threaten the one thing the genre and its devotees pride above all. Authenticity.

This precedent for authenticity was initially set in the genre’s first generation, an era that gave us acts like Jimmie Rodgers and The Carter Family. They became the traditional country prototype, not only in sound but also in image, one that was homespun and modest. While it would be viewed as the standard, this era of country was perhaps the most short-lived, merely a springboard for what the genre would become. When the next generation brought with it the age of the “barn dance” and the birth of the Grand Ole Opry, cowboy crooners like Gene Autry and Western swingers like Bob Wills would quickly alter this beloved paradigm.

Autry—donning his pearl snaps and crisp white cowboy hat—betrayed modesty for something glitzier. In marrying his film and music careers, he turned the once down-home style into something well-suited to the silver screen. There was also a shift in sound during this time, with Wills introducing drums to country music, an instrument that had previously been deemed too inappropriate for the genre. Against his Texas Playboys’ sacrilegious rhythms, the calls first came to “save country music”.

Departing from the days of “Blue Yodels” and sibling strummers did not mean a move away from authenticity. In pushing country music’s young—and still pliable—boundaries, artists like Autry and Wills were some of the first to prove there was room for growth.

However, by the end of World War II, drums and cowboy caricatures would be, quite literally, small change. Country music would witness a great rift in the 1950s as the genre splintered off into various subsects. At the start of country’s third generation, western swing and honky tonk were in heavy rotation, with different, more polished sounds soon joining the mix as the genre made its move toward commercialization. Styles like bluegrass became new frontiers during this time, including one that many regarded as unsavory.

An early form of rock and roll would infiltrate the genre, with spitfires like Jerry Lee Lewis and a young Johnny Cash fanning a rockabilly flame. They came fitted with an affinity for the great Hank Williams, who by that point had been barred from the Opry for his frequent drunkenness and no-show status. “Save country music”, the previous generation once again gasped, pearls in one hand as they waved farewell to that once unsullied portrait of a genre they had held so dear. Their country music was no longer clean-cut, no longer safe or comfortable. ‘Great Balls of Fire’ had scorched what security remained.

Growing pains were felt as the genre again stretched its young bones, making space for pompadours, blazing keys and men in black. But with this discomfort came progress. Rockabilly’s arrival may have ruffled feathers, but by showing that country music could stand to have a rougher edge, artists like Lewis and Cash gave the genre a fighting chance.

With the arrival of the 1970s, country only fractured further, the genre virtually splitting in two. What had been effectively weeded out and watered down over the previous decades into the commercially acceptable “countrypolitan” sound – led by the likes of Chet Atkins and company – stood on one side of the fissure. Inhabiting the other was a band of Nashville outliers known as the Outlaws, who emerged as a direct result of Music City’s venture into what was profitable and ultimately regarded as soulless. Many believe these outlaws – Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, et al – heeded the call to save the genre’s soul, materializing as the generation’s redeemers, attempting to liberate country music from its own fattening pockets.

In reality, Nashville had become a corporate machine. While that meant country music was finding favor among broader audiences, it was believed to be at the expense of that long-exalted authenticity. Songs were meeting the airwaves fresh off the RCA Victor conveyer belt, all glossy and unblemished with that same weepy ‘Stand By Your Man’ perfection. Did that mean the genre needed rescuing, then? The Outlaws seemingly didn't believe so. They didn’t come to save country music; they came to make it on their own terms. The Outlaws and their music merely acted as the great equalizer, reminding us that country was allowed to be imperfect and unpolished and could still be just as favorable.

Over the next several years, country music continued to enjoy a fair amount of commercial appeal. By the 1990s, it had exploded, with the genre beginning to witness stadium-sized success. Acts like George Strait, Garth Brooks and Shania Twain headed the generation in which country officially crossed over, invading the pop charts and possibly forever blurring the line between what qualified as country and what didn’t. As their music became increasingly appreciated the world over, these artists began selling out bigger and better venues. Perhaps to purists, that meant the genre had sold out too. “Save country music”, purists bellowed, this time against a barely recognizable sound, one now buried under all the pomp of pop.

Pop didn’t put the genre in danger—far from it. This era gave the style new life, keeping it relevant during a time when cushy, glossy arrangements and simple hook-driven lyrics dominated the collective consciousness. Because of this generation and its love affair with pop, country music entered the new millennium guns blazing.

Through the late 2000s and much of the 2010s, country artists continued to borrow, pulling influences from pop, hip-hop, and rock in an attempt to further the chart-topping accomplishments of their predecessors. While the Lady As and the Carrie Underwoods of the world dominated, the Florida Georgia Lines and the Jason Aldeans of the industry gave life to bro-country and country rap in return.

Suddenly, the country music we were trying so hard to save became that much more difficult to find against these beer-guzzling soliloquies. That was until the rise of purveyors like Sturgill Simpson, Tyler Childers, and Margo Price gave reason to rejoice. Once again, it was believed the saviors had come. Much like in the days of the Outlaws, Music City had been consistently turning a profit, churning out tunes that were now nearly indistinguishable from those of country’s past. Still, that didn’t mean the genre needed resuscitating, nor did it mean this new batch of “saviors” had come to do anything of the sort. Rather, they created a balance.

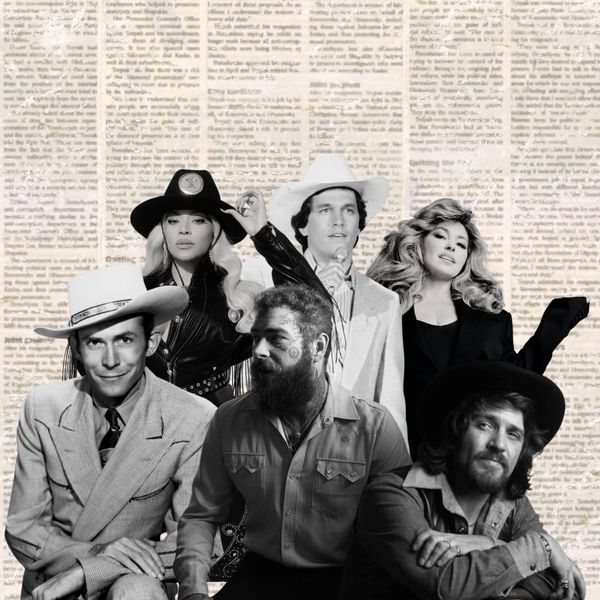

Now, in the 2020s, we may very well be witnessing the coming of country music’s latest generation. It is an exciting, anything-goes moment, as already established global stars like Beyoncé, Post Malone and Lana Del Rey make their foray into the genre. However, those same words—now tired but still just as insistent—have begun to resound beneath the backbeat of songs like ‘TEXAS HOLD ‘EM’. “Save country music”, the sentiment now arrives via social media, vitriolic comments proselytizing what is and isn’t country.

If the last hundred years of the genre have told us anything, it’s that country can be anything it wants to be. Today, no one bats an eye when they hear a drum beat in a country song or when their twang also comes with a little rock or pop. That’s because decades of change and generations of changemakers are the only reason we have the genre we have now.

At some point, we’re going to have to stop trying to save country music and accept that the genre, like all art, is ever-evolving. Like any other style of music, it has to change and adapt in order to not only survive but thrive.

--